Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 36, n. 3, Sept./Dec. 2023

The archive as object: written culture, power, and memory | Thematic dossier

The history of imperial Recife through its municipal postures

The thread woven in historical archives

La historia del Recife imperial a través de sus posturas municipales: el hilo tejido en los archivos históricos / A história do Recife imperial por suas posturas municipais: o fio da meada tecido em arquivos históricos

Maria Angela de Almeida Souza

PhD in History from the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE). Professor in the Postgraduate Program in Urban Development in the Department of Architecture and Urbanism at UFPE, Brazil.

ABSTRACT

This article aims to demonstrate the importance of research in archives for history writing. It describes the journey undertaken to capture documents archived in various collections to report the history of Recife, based on the norms established by its City Council, in the Brazilian imperial period, codified as postures and destined to regulate the construction of the city and to organize urban activities, and presents this historical account emphasizing documentary research.

Keywords: historical archives; municipal postures; Brazilian Empire; Recife history.

RESUMEN

Este artículo tiene como objetivo demostrar la importancia de la investigación en archivos para la escritura de la historia. Describe el recorrido emprendido para capturar documentos archivados en diversas colecciones para relatar la historia de Recife, a partir de las normas establecidas por su Ayuntamiento, en el período imperial brasileño, codificadas como posturas y destinadas a regular la construcción de la ciudad y a organizar actividades urbanas, y presenta este relato histórico enfatizando la investigación documental.

Palabras clave: archivos históricos; posturas municipales; Imperio brasileño; historia de Recife.

RESUMO

Este artigo objetiva demonstrar a importância da pesquisa em arquivos para a escrita da história. Descreve o percurso empreendido para captar documentos arquivados em diversos acervos para relatar a história do Recife, pautada nas normas estabelecidas pela Câmara Municipal, no período imperial brasileiro, codificadas como posturas e destinadas a regulamentar a construção da cidade e a organizar as atividades urbanas. Apresenta esse relato histórico enfatizando a pesquisa documental.

Palavraschave: arquivos históricos; posturas municipais; Império brasileiro; história do Recife.

Introduction

The aim of this article1 is to highlight the importance of researching archives in order to capture the thread that weaves history together. It focuses on the research carried out to write the history of Recife during the period of the Brazilian Empire, based on the rules established by the city council to order the construction of the city and discipline urban activities, codified under the name of postures. It describes the research process in the archives and presents the historical narrative of Recife, focusing on the documentation collected.

The documentary research for this article was defined on the basis of the central object of the historical account to be constructed ‒ the municipal ordinances of Recife ‒ and the delimited time frame ‒ the period of the Brazilian Empire. The research path, in turn, was fueled by the reading of extensive thematic bibliography related to the object, which pointed to the need to broaden, without losing focus, not only the documentary sources, but also the time frame. Within the scope of the broader study on which this article is based, the research extends to look for the genesis of Brazilian municipal ordinances in the colonial period, based on the Portuguese legal framework; as well as to look for the new ways of legislating the city, which are installed with the Brazilian republican period. In the text presented here, only a brief reference is made to these periods.

The historical narrative presented in this article, emphasizing the documentary base collected in the archives, highlights two processes that go hand in hand: on the one hand, the enshrinement of Portuguese memory in Brazilian municipal ordinances in the imperial period; and, on the other, the expression of the specificities of the local process in Recife’s municipal ordinances, highlighting the actions of municipal management. This second aspect, the historical documentation that was the object of the research in the archives, was fundamental in defining the middle of the 19th century as a milestone of change in these regulations, when hygiene concerns began to take priority over aesthetic concerns.

As this is a study of a society based on documentation established over a long period of time, the research carried out includes institutional processes (established norms) that deal with objects of different temporalities: on the one hand, they refer to elements subject to inertia, not only built structures, but also some traditions, which time takes to wear down; and, on the other hand, they contemplate the lifestyles and behaviors of citizens, susceptible to shorter changes. Thus, the writing of Recife’s history takes into account what Braudel (1958) says, that certain events and transformations in long‒term history are characterized by a series of common traits, while others cause ruptures that renew the face of the processes. These ruptures can occur without breaking the thread that characterizes, in broader terms, the period in which they are inserted, or they can break the structures that define that period, defining a new historical moment.

In this direction, Foucault (1972) pays special attention to the discontinuity that such a rupture causes in the processes, since he favors the ruptures and disjunctions seen in history, highlighting the differences (rather than the similarities) between the various eras. It is from this author’s perspective that the analysis of historical documentation, supported by extensive historiography, guided the construction of the history of imperial Recife.

By adopting the path of urban legality, this historical account of imperial Recife seeks to elucidate, from Rolnik’s perspective (1997, p. 13), the constitution of a powerful web, “invisible and silent”, which runs through all the processes of building and organizing the city. He reveals that, in Brazil, the planning and disciplining of the territory of towns and cities has always been under the aegis of the municipality. The municipal councils, which since colonial times have been given the task of establishing ordinances for urban planning, underwent changes in their structure and attributions during the imperial period. Despite being subject to the provincial government, they continued with their legislative attributions of disciplining the daily exercise of urban activity, regulating the construction of common buildings, mostly entrusted to building masters; and regulating customs and procedures for living in the urban space, as well as the use of public space in the day‒to‒day life of the city.

The approach adopted here, adapted to the article format, highlights two aspects that correspond to the central items on which the text is structured. The first item describes the course of the research, undertaken in numerous historical archives, of different natures and dispersed in various collections. It highlights not only the path undertaken in the archives to fill in gaps in information, based on clues and indications found in the documents researched or in the historiography of reference, but also the use of other sources (iconographic, literary, etc.) that give intelligibility to the narrative. The next item presents the historical account of imperial Recife, based on this research, whose central object refers to the postures established by the City Council. The privilege given in this article to the information obtained from documentary research, to the detriment of the extensive and valuable historiography on the topics covered, is intended to demonstrate the importance of the diversity of the sources researched for elucidating the historical process, highlighting the centrality of the archives in the account presented.

The search for historical records: archives as an object

The documentary base on which the historical account of imperial Recife is based consists mainly of the archives of official documents, where the municipal regulations governing the construction and activities of the city are recorded, as well as other complementary official documents, such as imperial and provincial laws, minutes, correspondence and administrative reports related to these regulations.

The research begins with the ordinances established by the Câmara Municipal do Recife [Recife City Council], the central object of the history to be constructed, which had to be recorded in a book of their own, both in the colonial period and in the Empire, according to the official documents. In an “Act of Council” of the Recife City Council, dated June 26, 1762, it is recorded that

all republicans and summoned for the purpose of settling and reducing the postures of this Senate because they were found to have some inconveniences in offense of the same Senate and the republic and all uniformly settled on the postures that were written in a separate book in which they also signed.2

Article 5 of the imperial law of October 1, 1828 (title II ‒ Municipal Functions) also made this practice mandatory, which had already been in place since colonial Brazil, stating that: “The indispensable books are: one for recording the ordinances in force and another in which to record the present law and all the articles of those that are published that concern the councils” (Brasil, 1996, p. 41, emphasis added).

However, despite an exhaustive search in the archives of the city of Recife and the city of Rio de Janeiro (the capital of the Empire, where copies of the documents from the provinces), none of the record books for Recife’s municipal ordinances were found. On the contrary, the Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro [General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro] had the city’s ordinance books available, which cover the imperial period, starting with the law of October 1, 1828, which regulates municipal councils (1830‒1889). This meant that we had to look for other alternative sources and archives to capture the records of Recife’s ordinances, confirming what Foucault (1979) said about historical studies requiring meticulous care and patient documentation.

In order to search for Recife’s municipal ordinances in various sources, we took into account that, as determined by the imperial government, the ordinances had to be submitted for approval by the Provincial Council (1828‒1835) and, later, by the Provincial Assembly, which replaced this Council (1835‒1889), and were published as part of the provincial laws (1835‒1889). Under the terms of the imperial law of October 1, 1828, article 72, “the said postures will only be in force for one year until they are confirmed, at which end they will be taken to the general councils, which may also alter or revoke them” (Brasil, 1996, p. 44).

Based on these determinations, the main source researched became the Coleção de leis, decretos e resoluções da província de Pernambuco [Collection of laws, decrees and resolutions of the province of Pernambuco]3 ‒ made up of several books in the collection of the Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano [Jordão Emerenciano State Public Archive] (Apeje) ‒ where the 2,149 laws of the province of Pernambuco from 1835 to 18894 are published. At the end of the research, 586 provincial laws of interest to the management process of the city of Recife were identified and recorded for analysis, including forty by‒laws of the Câmara Municipal do Recife. However, some of these Recife ordinances, published as laws of the province of Pernambuco, made references to others that were not published, pointing to gaps to be researched in other sources.

The new searches took into account the provisions of article 17 of law n. 16 (additional act) of August 12, 1834, according to which the president of the province had the power to approve a bill that he thought should be sanctioned, but which had been presented at a time when the General Assembly was not meeting: “If the General Assembly is not meeting at that time and the government believes that the bill should be sanctioned, it may order that it be provisionally executed, until the General Assembly makes a final decision” (Brasil, 1996, p. 51). Under the terms of the law, this was provisional approval until the Assembly’s final decision.

The research expanded to include the Correspondências da Câmara Municipal ao Presidente da Província [Correspondences from the City Council to the President of the Province]5 ‒ manuscripts archived in books that also make up the collection of the Apeje, as well as loose documents from the Arquivo da Assembleia Legislativa de Pernambuco ‒ Projeto Memória Legislativa [Archives of the Legislative Assembly of Pernambuco ‒ Legislative Memory Project], where we found complete texts of postures provisionally approved by the president of the province, whose definitive approval was included in the Annexes of the Provincial Laws, without the express content of their terms.

The need to go back in time to find postures not only in the early phase of the Empire, when Brazil was responsible for constructing its own laws, but also in the transition between the colonial and imperial periods, required research into the Atas de Vereação da Câmara Municipal do Recife [Minutes of the Recife City Council]6 ‒ manuscripts compiled in collections archived at the Instituto Arqueológico, Histórico e Geográfico de Pernambuco [Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Institute of Pernambuco] (Iahpe). On the other hand, some clues pointed to new sources through which the gaps identified in the sequence of ordinances could be filled. These include several copies of the Diario de Pernambuco ‒ the city’s most widely circulated newspaper at the time ‒ archived on microfilm at the Fundação Joaquim Nabuco [Joaquim Nabuco Foundation] (Fundaj). This newspaper was responsible for publishing the official acts of the government in its various instances, complying with the explicit stipulations of the law of October 1, 1828, title II ‒ Municipal Functions: “Subscribers shall be made to the Diaries of the General Councils of the Province, those of the Legislative Chambers and the periodicals containing extracts from the sessions of the Municipal Chambers of the Province, if any” (art. 61); and “The Town Councils [...] shall draw up their ordinances, which shall be published by public notices, before and after they are confirmed” (art. 71) (Brasil, 1996, p. 42; 44, emphasis added).

In the manuscripts of the Correspondências da Câmara Municipal ao Presidente da Província, we found the appointment, on August 12, 1830, of the German engineer João Bloem,7 who played a key role in the Câmara Municipal do Recife. We also found, in their entirety, the Posturas adicionais da arquitetura, regularidade e aformoseamento da cidade [Additional Regulations on the Architecture, Regularity and Shaping of the City],8 dated October 12, 1839, responsible for establishing the rules of aesthetic composition and construction of Recife’s townhouses, established under the management of the aforementioned engineer, as well as the Posturas adicionais polícia das ruas [Additional Police Regulations for the Streets],9 dated November 25, 1839, which incorporate a large part of the provisions of the regulations. In the microfilms of the Diario de Pernambuco, we found three edicts10 regulating the construction of buildings in Recife, published by João Bloem in the three months following his appointment in 1830, as well as a complete Código de Posturas do Recife [Recife Code of Ordinances],11 dated September 23, 1831, with a wide range of rules and precepts, comparable to the first Code of Ordinances published in Rio de Janeiro in 1830. Everything leads us to believe that this is the first Code of Ordinances of the Recife City Council in the imperial period, formulated under the conditions imposed by the aforementioned imperial law of October 1, 1828, which consolidates the various ordinances published in public notices since the colonial period.

In order to contextualize and find meaning for Recife’s various municipal ordinances, the research carried out for the broader study on which this article is based was expanded to look for the bases of colonial municipal ordinances in the Portuguese legal framework. The urban content of the Portuguese kingdom’s ordinances, published by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (1998), was analyzed in order to characterize the legal‒urban nature and institutional basis of the Portuguese ordinances transported to colonial Brazil. In order to contextualize the regulations established specifically in the imperial period, the following were consulted: the Anais da Assembleia Legislativa de Pernambuco [Annals of the Legislative Assembly of Pernambuco],12 the Relatórios dos Governadores de Província enviados à Assembleia Legislativa [Reports of the Provincial Governors sent to the Legislative Assembly]13 and the Correspondências da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco [Correspondence from the Recife City Council to the President of the Province of Pernambuco],14 among others.

Some historical records that portray the city in its various eras were also sought: the city’s iconographic archives, with images of Recife produced by Bauch, L. Schlapriz and L. Krauss, whose drawings were lithographed by F. H. Carls. Carls, were used as a testimony of the city, to support the analysis of the aesthetic postures of Recife in 1839 (Ferrez, 1956; 1981; 1984); and some literary archives, which include accounts by foreigners who were in the city during the imperial period: the Englishmen Henry Koster, in 1816 (Koster, 1978) and Maria Graham, in 1821 (Valente, 1957), the American Daniel Kidder, in the 1840s (Kidder, 1943) and the Frenchmen Louis Tollenare, in 1816‒1817 (Tollenare, 1978) and Louis Vauthier, in 1840‒1846 (Vauthier, 1943). The latter, a French engineer who played an important role in the modernization of Recife in the mid‒19th century, he left personal notes in a diary in which he describes and draws the townhouses of Recife.

The history of imperial Recife, written from its municipal ordinances, thus seeks to contextualize the established norms with records drawn from official reports, travelers’ accounts and professionals who participated in the life of the city, as well as images that portrayed it at different times. It emphasizes the importance of the diversity and originality of documentary sources, as well as the document itself, as the fabric from which the various relationships established between the events that make up history are drawn. It is in line with the ideas of Foucault, who, when commenting on the status of the document for history, states that

the document, then, is no longer for history that inert matter through which it seeks to reconstruct what men have done or said, what has passed and of which only the trace remains: it seeks to define, in the documentary fabric itself, units, sets, series, relationships. (Foucault, 1972 apud Machado, 1981, p. 71)

The document that bears witness to history, according to Foucault (1979), can be broken down into elements that need to be isolated, grouped, made relevant, interrelated and organized into sets. For this author, analyzing the fabric of documents presupposes the task of distinguishing historical events according to their scope, differentiating the networks and levels to which they belong and, from there, relating them in order to reconstitute the threads that connect them and make them engender, one from the other, the fabric of history.

The history of imperial Recife built from the archives: an account in two sections

In this article, the history of the city of imperial Recife, based on the records of its municipal ordinances, focuses on the contributions of the documentary base, without, however, dispensing with a brief dialog with historiography, in order to support the two aspects highlighted in the text: the enshrinement of Portuguese memory in the legislative framework of Brazilian municipalities, at a time when imperial Brazil was constituting itself as a nation; and the specificities that, in parallel, go on to highlight particular characteristics in Recife’s municipal ordinances, arising from processes established in the city and the actions of municipal management.

The focus of the analysis was the repercussions of municipal regulations on the city’s buildings, showing that the effort to establish the aesthetic principles of Recife’s sobrados in the early decades of the Empire were replaced by hygienist concerns that redefined building standards in the second half of the 19th century.

The Portuguese memory enshrined in municipal ordinances in the Brazilian Empire

The urban planning laws of Brazilian municipalities and, as such, of the city of Recife have their historical origins in the municipal ordinances of the colonial period and their genesis goes back to the Portuguese municipalities, whose local administration was initially carried out through the representative councils of the communities. Portugal, like the entire Iberian Peninsula, is heir to the Greco‒Roman tradition of written law, which predominates over the Germanic tradition of customary law, based on uses and customs, brought by the Visigoths. This predominance led to customs being compiled, consolidating the deliberations of magistrates and popular assemblies in the form of postures (Langhans, 1937).

In the 15th century, the Portuguese kingdom’s ordinances ‒ Afonsinas (1446), Manuelinas (1505) and Filipinas (1603) ‒ legally consolidated the political and social transformations taking place between the royal power and the municipal councils, in a slow process of administrative centralization and consolidation of the Portuguese state. The General Laws of the Kingdom then established the basic provisions to be dealt with in municipal ordinances. In that same century, the treatment of urban issues, with urban planning principles already based on the ideas of the modern period, was incorporated into the General Laws of the Kingdom and was expressed, with the necessary updates, in the ordinances of Portuguese cities and overseas colonies, including Brazil until the 19th century, extending, in some of these, into the 20th century.

In the organization of Brazilian cities, from the very beginning, the municipality was set up with its normative instrument ‒ the municipal ordinances ‒ based on the ordinances of the Portuguese kingdom. Thus, unlike in Portugal, the political organization of local nuclei in Brazil preceded their social organization. Brazilian towns and cities emerged under administrative prescriptions, through a charter granted by the king or governor, often before they were founded (Zenha, 1948).

Recife differs from most of the towns and cities established in Brazil in that it arose as a settlement near the port, part of the territory of the town of Olinda, the seat of the captaincy of Pernambuco. It developed as an urban center during the Dutch invasion (1630‒1654), returning to the jurisdiction of the Olinda City Council after the restoration of Portuguese rule. It only became a municipality in 1710, when it was elevated to the category of town and its own town council was set up.

According to Salgado (1985), town councils could only be set up in places with town or city status.15 This author points out that some received the honorific title of Senate of the Chamber, although this title did not differentiate them in terms of their administrative attributions and powers. This led Pereira da Costa (1966, l. 6, p. 329) to refer to the city council of colonial Recife as “Câmara do Senado do Recife”.

The Recife City Council, which at the beginning of the Brazilian imperial period was just over a century old, functioned like the other municipal councils in Brazilian cities and towns, which, as Zenha (1948) emphasizes, stood out for being set up according to Portuguese tradition, under the rule of its Major Law, while at the same time imposing a new process that often escaped the rule and control of the Crown, requiring council officials to interpret the rules imposed in the face of the peculiarities of local processes.

As Marx (1991) points out, the chambers of Brazilian municipalities had an undeniable influence on local political organization, taking on important government, administration and justice duties. They also played a decisive role in founding and organizing cities. They distributed land, carried out public works, as well as establishing ordinances, setting rates and judging verbal insults, among other actions.

At the beginning of the Empire, the law of October 1, 1828 (Brazil, 1996), called the Regimento das Câmaras Municipais [Municipal Councils Regulations], restricted the autonomy of the municipal councils, making them merely administrative institutions. The councils of Brazilian towns and cities then lost their power to judge, but retained the prerogative to formulate laws, as long as they submitted them to the provincial government for approval (Cortines Laxe, 1885). This 1828 law establishes, in its article 66 sets out the regulations to be complied with by Brazilian municipalities, mostly based on Portuguese ordinances, giving unity to the regulations of the various municipalities in Brazil. The 12 sections of article 66 state the following in full:16

1 ‒ Alignment, cleaning, lighting and unpacking of streets, quays and squares, conservation and repair of walls made for the security of public buildings and prisons, sidewalks, bridges, fountains, aqueducts, fountains, wells, tanks and any other constructions for the common benefit of the inhabitants, or for the decorum and ornament of the villages.

2 ‒ On the establishment of cemeteries outside the precincts of temples, conferring for this purpose with the principal ecclesiastical authority of the place; on the draining of swamps and any stagnation of infectious waters; on the economy and cleanliness of corrals and public slaughterhouses; on the placement of tanneries; on the deposits of filth and anything that may alter and corrupt the healthiness of the atmosphere.

3 ‒ On ruinous buildings, excavations and precipices in the vicinity of villages; ordering them to be marked to warn passers‒by; the suspension and throwing away of bodies that may harm or disgrace passers‒by; caution against the danger arising from the wandering of madmen, drunks, ferocious or vicious animals and those who, by running, may disturb the inhabitants; measures to prevent and put out fires.

4 ‒ On voices in the streets during quiet hours, juries and obscenities against public morals.

5 ‒ On weeds and those who bring loose cattle without a shepherd in places where they can cause any damage to the inhabitants or crops, the removal of reptiles, poisonous or any plant‒eating animals and insects; and, above all, the rest that concerns the police.

6 ‒ On the construction, repair and conservation of roads, paths, plantations of trees to preserve their limits for the communities of travelers, and those that are useful for the sustenance of men and animals, or serve for the manufacture of gunpowder and other objects of defense.

7 ‒ They shall provide places for cattle to graze and rest for daily consumption as long as the councils do not have them.

8 ‒ They shall protect breeders and all persons who bring their cattle to sell them against any oppression by the employees of the registers and pens of the councils where there are any, or by the dealers and merchants of this kind, punishing with fines and imprisonment, under the terms of title III, article 71, those who harass and annoy them in order to divert them from the market.

9 ‒ Only in public or private slaughterhouses, with a license from the town councils, may cattle be killed and butchered; and by calculating the breaking‒in of each steer, with the exactors of the duties imposed on the meat being present, the owners of the cattle will be allowed to drive them away after they have been butchered, and sell them for the prices they want and wherever they please, provided that they do so in conspicuous places, where the town council can check the cleanliness and healthiness of the butchers and the meat, as well as the fidelity of the weights.

10 ‒ They shall also provide for the comfort of fairs and markets, and the healthiness and wholesomeness of all foodstuffs and other objects exhibited for public sale, having scales to see the weight and standards of all weights and measures in order to regulate the measurements; and on what may favor the agriculture, commerce and industry of their districts, absolutely refraining from marking up the prices of goods, or placing other restrictions on the broad freedom which belongs to their owners.

11 ‒ Exceptions shall be made for the sale of gunpowder and all other goods susceptible to explosions and the manufacture of fireworks, which, due to their danger, may only be sold and made in the places marked out by the town councils and outside the town, for which the appropriate ordinance shall be made, imposing condemnation on those who violate it.

12 ‒ They may authorize public spectacles in the streets, squares and festivals, as long as they do not offend public morals, by means of some modest gratuity for the council’s income, which they will set by their ordinances (Brasil, 1996, p. 42‒43).

By making these 12 sections compulsory, the Regimento das Câmaras Municipais gave common elements to the ordinances of Brazilian municipalities, consolidating the provisions of the Portuguese kingdom. Thus, in the 19th century, both Brazilian and Portuguese cities had municipal ordinances regulating matters with provisions of the same content, as exemplified below.

(1) Ordinances relating to the construction of public roads, prohibiting the plastering or raising of sidewalks at the entrance to doors, under penalty of a fine, and requiring them to be repared at the owner’s expense.

Lisbon, Portugal, Lisbon Code of 1886: [...] for no purpose make recesses or crescents, in the sidewalks or on the sidewalks, at the entrance of any door.17

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Municipal Ordinance of 1830: All property owners who build will be obliged to pave their frontage with slabs 6 palms wide, according to the same leveling as the frontage street, without being able to pave above this level [...]. The sidewalks that are now made [...] will be lowered by their owners.18

Recife, Brazil, Municipal Ordinance of 1839: Within three months of the publication of the present Ordinance, all owners of urban buildings will repair the sidewalks of their houses (commonly and abusively called calçadas), these sidewalks will all keep the same level, demolishing all the stops.19

(2) Ordinances that deal with constructions that may endanger the safety of individuals, stipulating that the council must order the owner to demolish buildings that threaten to collapse, as well as to demolish balconies, porches, walkways, balconies or any constructions in the streets and lanes without the necessary license:

Pampilhosa da Serra, Portugal, Pompilhosa da Serra Code of 1868: When a building, wall or porch threatens to collapse, or it is known from its condition that it could harm neighbors or the public, the council, either by itself within the town, or by the janitors in other towns, must summon the owner to demolish the ruinous construction, under penalty of paying a fine of 1.00 réis and having the demolition carried out at their expense.20

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Municipal Ordinance of 1830: Any building, wall or covering, of any nature whatsoever, which is in a state of threatening ruin to the public or private individuals, will be demolished at the owner’s expense, when the respective inspector with two experts examines it and decides that it cannot be repaired [...].21

Recife, Brazil, Municipal Ordinance of 1849: All buildings, walls and coverings, of any kind, which are in a state of threatening ruin, shall be demolished at the owner’s expense, with the inspector carrying out a prompt examination by two experts in order to ascertain whether they should be demolished or repaired, and, once the examination has been carried out at the owner’s expense, he shall notify the owner to immediately carry out the demolition or repair within the time limit specified in the same document; and, once this time limit has expired, the said owner, attorney‒in‒fact or custodian shall be fined 10,000 rs., and the same inspector will notify the city attorney to carry out the demolition or repair at the owner’s expense.22

In addition to the content of the ordinances from the Portuguese codes, incorporated by the Rules of Municipal Councils (Brazil, 1996), other matters, based on local social processes, give peculiarities to the ordinances established by Brazilian municipal councils. Because it was a slave society, the bylaws contained discriminatory measures against the people of Brazil. to be demolished, must be demolished blacks. Recife’s Code of Ordinances of 1831,23 for example, forbade blacks from carrying bulky loads over the sidewalks, except if they were carrying people in chairs and hammocks or if the streets were flooded; forbade slaves from wearing “ragged” clothes; penalized slave owners who went out on the streets after curfew (9pm); and established a penalty of imprisonment with flogging for slaves found making a mess, among other provisions. These ordinances, with minor changes, were maintained throughout the imperial period, while other ordinances, more specific to each city, were incorporated into its legislative framework.

Recife’s specificities defining new municipal legislative frameworks

Two parallel processes, as the literature on the city points out, contributed to giving specificities to the postures of the Recife City Council: the city’s population expansion, when the number of inhabitants practically doubled in the third quarter of the 19th century;24 and the modernization processes experienced by the city, to which the impetus given to the country’s culture by the government of King João VI contributed. João VI, through activities linked to the supply of European models, the hiring of foreign masters and the recruitment of disciples through art schools and museums (Sodré, 1970). These processes had repercussions on the rules that established the city’s aesthetic standards in the first decade of the Empire, as well as on the sanitary measures adopted, which intensified from the middle of the 19th century onwards, driven by the major epidemics that followed in the 1850s and the advances in social medicine that focused on the urban environment.

In the first decades of the imperial period, alongside the customary postures from the colonial period, the aesthetic postures of Recife’s urban buildings emerged as a new development, regulating the city’s buildings; and in the second half of the 19th century, hygienist measures became evident, supporting the urban improvements that were being implemented in the city and discussing the health conditions of the sobrados. These two dimensions ‒ aesthetic and hygienist ‒ characterize the specificities of the ordinances of imperial Recife, as will be presented below, focusing on the ordinances relating to the city’s buildings.

The aesthetics of buildings

In 1830, recognizing the lack of qualified technical personnel to carry out the duties conferred by the law of October 1, 1828, the Recife City Council hired the engineer João Bloem to be in charge of the city’s architecture. In 1830, he published a notice in the local press to make the city’s inhabitants aware of the ban on any construction and “arbitrary architecture”25 in the central districts of Recife, Santo Antônio and Boa Vista. From then on, all the houses and streets had to follow the plan drawn up by the engineer, who was authorized to prevent the old houses from being rebuilt, except along the new alignment and in accordance with the architecture of the plan.

The toecaps26 of Recife’s colonial houses became the object of the first campaign undertaken by the military engineer Bloem, who, in 1830, defined the rules for the architectural composition of the city’s single‒storey houses and townhouses, establishing the height of the buildings, as well as the height and width of doors and windows, and imposing the reform of the gables and the placement of platbands27 with cornices.28

Single‒storey houses will be 20 palms high from the threshold to the surface of the parapet, from the surface of the first floor to that of the second, 20 palms high, from the surface of the second floor to the third, 18 palms high, and from there upwards they will be reduced by 1 palm for each floor; the jambs will be 12 ½ palms high; both doors and windows will be the same height, and 6 palms wide; they will not have eaves or overhangs, but cornices. And so that everyone may know about it, I have sent this notice, posted it in the usual places, and published it in the press on November 15, 1830.29

In 1839, the City Council published an extensive set of rules for the architectural composition of buildings, called Posturas adicionais da arquitetura, regularidade, e aformoseamento da cidade,30 which set the standard for the composition of the façades of townhouses located in the central districts of Recife, demarcating a new attitude towards the ordering of urban space. In short,31 these elements are available:

Regarding streets, determining that building permits would be required based on the survey of the street plan and the demarcation of street widths by posts (art. 1), and establishing minimum street widths (art. 2);

On blocks, defining a new urban grid pattern (art. 3);

On building structures, expressing a concern for the foundations (art. 5); obliging the simultaneous construction of the four walls of the building (art. 6); making the masters of private works responsible for damage caused by the poor quality of the building (art. 20);

On the relationship between buildings and roads, establishing measures relating to vehicular traffic (art. 12); providing for the disposal of wastewater and rainwater (art. 16), the placement of stone sinks and drains in backyards (art. 17); the placement of pipes, by the councils, in the width of the crosswalks, belonging to double‒fronted houses (art. 21).

On the rules of urban composition, with the façades of buildings as the central object, and extending to the sidewalks of the streets:

‒ by obliging corner buildings to submit their street fronts and crosswalks to the rules established by the ordinance, thus guaranteeing the same aesthetic standard on all streets ‒ main and secondary ‒ in the city (art. 4);

‒ by establishing the maximum height of buildings and corner houses (art. 7);

‒ by establishing the number and measurements of doors and windows, as well as the requirement for running balconies on floors above the first floor (art. 8), as well as the requirement and heights of cornices, with a mold provided by the city council (art. 9);

On the obligation to cordon off the height of the thresholds, the height of which would be defined by the city council when the building permit was issued, which would also be responsible for providing “leveling and cordoning, as well as all other symmetrical precepts” (art. 10);

On the possibility of building dormer windows (art. 11);

On the obligation of these rules for new floors added to houses already built (art. 13);

The obligation for walls to be built in the street to have the same dimensions, perspective, symmetry and regularity as buildings (art. 14), as well as the obligation for walls, ramparts and building walls to be plumb (art. 19);

On the obligation to provide street sidewalks with flagstones, establishing the width (art. 18); and finally,

On buildings in streets that had already been built that did not deviate considerably from the symmetry determined in these regulations (art. 15).

The façades of buildings take center stage, both in their relationship with the street and in the elements that make them up ‒ the maximum height of buildings; the number and size of doors and windows; the obligation to have running balconies, cornices32 and cords33 at the height of the thresholds, etc. The definition of these cordons is entrusted to a specific professional from the City Council, called a “cordeador”, who is responsible for defining the level of the floors of new buildings in relation to the height of the streets.

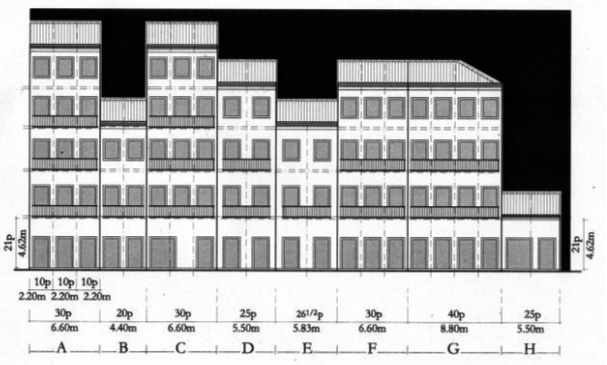

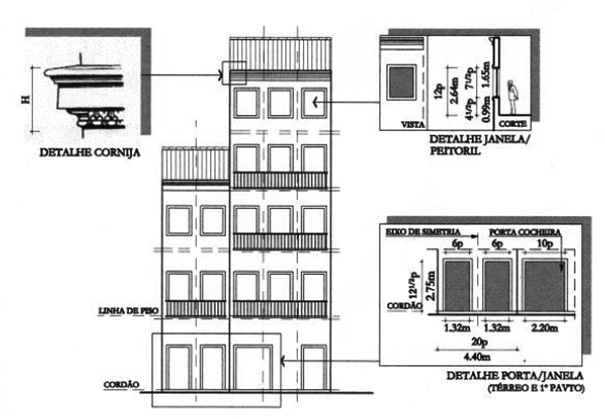

As an example of the aesthetic standard of the façades of Recife’s sobrados, established by the aforementioned additional Posturas da arquitetura, regularidade, e aformoseamento da cidade,34 of 1839, a schematic drawing of buildings with different widths and number of floors was drawn up (Figure 1), based on an excerpt from a photograph of the sobrados in Rua da Alfândega, in the Recife district. In addition, details of a cut‒out of two sobrados from this drawing are presented (Figure 2), demonstrating the plastic intention of these postures, as well as the regularity, standardization and rigorously symmetrical layout imposed on the architectural elements of the city’s building façades.

Figure 1 ‒ Drawing of buildings according to the rules established by the Postura da Câmara Municipal do Recife of 1839. Source: prepared by the author, with reference to a photograph of the sobrados in Rua da Alfândega, in the Recife district

The guiding principles of Recife’s aesthetic postures, published in 1839, refer to the principles of classical urbanism, whose foundations date back to the Renaissance period, as Choay (1985) states. The façades and their elements obey the idea of order and geometric discipline. The urban design and composition strategies used include: symmetry, referring to one or more axes; perspective; and the integration of individual buildings into harmonious architectural ensembles, with the facades of the townhouses outlining the street. These strategies of urban composition define the external appearance of Recife’s houses.

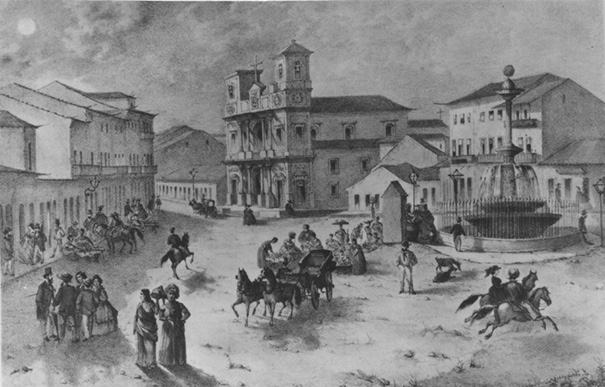

A search through Recife’s iconographic archives helps to analyze the applicability of these aesthetic rules to the city’s buildings. For the purposes of this article, images were selected from the lithographs by artists Luís Schlapriz and Luís Krauss, who used photography of a stretch of the city of Recife, Largo da Boa Vista, overlooking Rua da Imperatriz, the beginning of which is the Igreja da Boa Vista (Ferrez, 1981; 1956).

Figure 2 ‒ Details of the architectural elements of the buildings, according to the rules established by the Postura da Câmara Municipal do Recife of 1839. Source: author’s elaboration

When comparing Schlappriz’s engraving (Figure 3) with the lithograph drawn by Krauss (Figure 4), it can be seen that the group of old townhouses on the left has been renovated according to the aesthetic standards established in the aforementioned regulations, in the period between the two decades that separate these images.

It is important to mention that article 15 of the 1839 aesthetic postures takes into account the conditions already established in the city’s built space, when it states that “in the streets already built, whose buildings do not deviate considerably from the symmetry determined in these postures, the cordeador will regulate the new buildings by those, which in the judgment of the City Council come closest to it”.

This provision suggests that the aesthetic reading of existing buildings served as the basis for defining the rules established in Recife’s aesthetic ordinances of 1839. The dominant aesthetic pattern in the buildings on the important streets may have been adopted as a reference for the city’s built space. This pattern remained in force until the third quarter of the 19th century, when hygiene concerns called into question the existing pattern of the city’s sobrados in favor of hygienic building conditions.

Figure 3 ‒ Praça da Boa Vista (1858‒1863). Author: L. Schlappriz. Source: Ferrez, 1981. Archive: Fundaj

Figure 4 ‒ Rua da Imperatriz (1878). Author: L. Krauss. Source: Ferrez, 1956. Archive: Fundaj

The hygiene of buildings

The installation of the Public Hygiene Commission in the province of Pernambuco in 1850, under the chairmanship of the sanitary doctor Dr. Joaquim d’Aquino Fonseca, marked a new moment in which sanitary concerns in the city predominated and demanded greater participation by the Recife City Council, either through its ordinances or its inspection, in the issue of public health, extending hygienist concerns to the city’s buildings.

Machado (1982) comments that hygienist thinking in the 19th century identified the source of illness in two ways: on the one hand, the city became ill through contact with the fumes exhaled by the dead in church interiors, the living in hospitals and asylums, the perspiration of workers in factories and the butchering of animals in slaughterhouses; on the other, institutions were contaminated by the sources of contagion.

This thinking is based on a theory that, according to Corbin (1987), dates back to the mid‒18th century and gained rapid and lasting acceptance in European scientific circles. This theory argued that “miasmas” from pus, waste, manure and rotting corpses could corrupt the balance of vital forces, leading the body to all sorts of infections and even death. Based on this conception, as Corbin (1987) emphasizes, smells then began to be seen as directly responsible for at the same time that the olfactory sensation takes on a much deeper dimension than merely indicating the presence of an unpleasant smell.

From this perspective, the Public Hygiene Commission attributed the unhealthiness of the city of Recife to the emanation of “miasmas”.

It is true that, during the night, the westerly wind brings to the city the miasmas that during the day are released from these swamps, which occupy a large part of the surface, extending from Olinda to Rosarinho, and from Afogados to Piranga and adjacent places, miasmas that accumulate in the upper regions of the atmosphere; and this consideration should not be overlooked, because it greatly influences public health.35

Based on this concept, the Commission recommended the landfilling of floodplains, as well as other measures that were incorporated into the sanitary regulations that followed in Recife, either to comply with the hygiene requirements proposed by the Commission, or to support the sanitary infrastructure services promoted by the provincial government. Thus, as Foucault (1979, p. 86) would say, the city starts to be “scrutinized”, toured, observed by the City Hall officials and then standardized. As an object of healing, it involves its external space, as well as its buildings and institutions ‒ the cemeteries, markets, slaughterhouses, in short, the institutions where the population congregates, whether for productive activities, healing or death.

Due to Recife’s population expansion in the second half of the 19th century, as well as the precarious conditions of the basic sanitation systems (Zancheti, 1989), in a context of concerns about the city’s hygiene, the provincial government undertook the installation and expansion of water supply and sewage systems.

In order to support these initiatives, the Recife City Council established numerous sanitary regulations, published in provincial laws (LP),36 which determined measures to make sanitary installations in buildings feasible, with the aim of supporting the services of Carlos Luiz Cambrone’s37 company, which had signed an agreement with the provincial government to implement Recife’s sanitation infrastructure (LP n. 552/1863); regulate the channeling of rainwater (LP n. 797/1868, LP n. 1.020/1871); provide for measures to dispose of garbage (LP n. 1.176/1875; LP n. 1.777/1883); regulate the transportation of corpses (LP n. 351/1854); control foodstuffs and the hygiene and marketing of these products and regulate butchers’ and markets, the slaughter of animals and the supply of foodstuffs (LP n. 180/1879; LP n. 1.733/1883; LP n. 1.934/1888), among other provisions.

With regard to the buildings themselves, as the focus of this article, provisions are already found in the Manueline ordinances of the Portuguese kingdom, which prohibit “tolerating fire to any other neighbor” (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1998, l. I, t. XLIX, § 26 and l. I, t. LXVIII, § 24) testify to the awareness, present since the 15th century, of the need to preserve the entry of light into buildings, which subsidized the regulation of neighborhood relations ‒ the reciprocal rights and duties of neighbors ‒ in Portuguese legislation and, later, in the Brazilian Civil Code of 1916. But the fight against the unhealthy conditions of the sobrados takes on great importance from a document drawn up by the Pernambuco Public Hygiene Commission ‒ Bases for a general plan for the city’s buildings38 ‒ delivered to the Recife City Council in 1854, which suggests measures to sanitize the city’s buildings, which are incorporated into the council’s ordinances. According to the recommendations of the hygienist engineer Aquino Fonseca, the measures to be adopted by the City Council imply a general change in the building system of the city of Recife.

From the descriptions of the capital of Pernambuco in the first half of the 19th century, from visitors or professionals who worked in the city, we can get an idea of the urban conditions in the region during this period. The Frenchman Louis‒François Tollenare (1978, p. 21), who visited the city in 1816, commented that “the district of the peninsula, or Recife proper, is the oldest and busiest, and also the most poorly built and the least tidy [...] the houses have from two to four floors with three windows on the façade”. The Englishwoman Maria Graham recorded in her diary in 1821, published by Valente (1957, p. 102), that: “On the first floor are the stores, negro quarters and stables. The second floor is generally occupied by offices and warehouses, while the second is reserved for residences. The kitchen is always in the highest part, so that the lower floors are kept free from the heat of the fire”. The American Daniel Kidder (1943, p. 115) recorded that among the sobrados there were “six‒storey houses of a style unknown in other parts of Brazil”.

The French engineer Louis Vauthier, who arrived in Pernambuco in 1840, also recorded accounts of Recife that well characterized its neighbourhoods, streets and buildings. He became head of the Public Works Department between 1842 and 1846, carrying out significant works, including the design and construction of the Santa Isabel Theatre, which marked the city’s modernization process. In the letters that this engineer wrote about “the houses of residence in Brazil”, he referred to the streets of the Recife neighborhood:

This neighborhood retains, more than all the others, the mark of the old building system. You see these narrow, poorly aligned streets. (Vauthier, 1943, p. 138)

If the streets that border the facades in this neighborhood seem narrow, the alleys that connect them are even more so. You can see from the layout that they are no more than 4 to 5 feet wide. A pack animal wouldn’t pass through them. They are veritable cesspools that the foot and the sense of smell of the passer‒by carefully avoid. (Vauthier, 1943, p. 139)

And then, what are these elongated constructions that only receive air and light at both ends? This rigid form, this single type, compressed in width, does not lend itself at all, you understand, to a great variety of internal arrangements. So anyone who has seen one Brazilian house has seen almost all of them. (Vauthier, 1943, p. 143‒144)

Recife’s sobrados, at the time narrow and long, semi‒detached on both sides, three to six stories high, common in the streets of the city’s central districts, received direct lighting and ventilation only from the front ‒ from the street ‒ and from the back ‒ from the backyards. The alcoves, where people retired to sleep, were built into the interior of the sobrados, without receiving direct wind or sunlight. This layout, common to almost all Recife’s houses, made it difficult to implement the reform of the city plan demanded by Aquino Fonseca, who warned the Recife City Council officials about the precarious sanitary conditions of the alcoves:

It is well known that when a large number of individuals live in a room that is not very spacious and whose atmosphere is not very well renewed, breathing alters the proportions of the constituent principles of the air, decreasing the quantity of oxygen and increasing that of carbonic acid gas, which is harmful to life: for this reason, in a room, even a spacious one, the air becomes impoverished very quickly, as long as it is not renewed and is breathed in by many individuals. Sunlight has a great influence on all organized beings, especially the human species; without it, the organism weakens, and life is extinguished before it has gone through its various phases.39

The hygienist Aquino Fonseca proposed new building standards, considering that epidemic outbreaks of infectious diseases were caused by the state of the atmosphere produced by poor local health conditions. In line with 19th century European thinking, based on the theory of miasmas, he highlighted the following as the most important factors to be observed in public health measures: “the quality of the water”, as a source of health, “direct sunlight” and “winds”, which modify the atmospheric air, dispersing the “miasma”.40 In view of this, he suggested that the city should have wide streets, running east‒west, with squares spaced apart, so that the miasmas would be dispersed and recommends that the Recife City Council establish a height standard for new housing, in accordance with the width of the streets, in order to allow for good sunlight and ventilation in all the dwellings. In his Relatório da Comissão de Higiene Pública, published in 1855, he comments:

It was undoubtedly with this in mind that the municipal ordinances determined what the height of each place of the houses in this city should be; but even so, they do not satisfy the hygienic prescriptions. Allowing houses of any height to be built without taking into account the width of the streets means that the circulation of air in those streets is interrupted or hindered, and deprives those houses of the necessary ventilation; in addition, sunlight, which is so necessary for good health, cannot be easily accessed in the rooms of houses situated in such streets, and certain services, being carried out on the heads of slaves, contribute to the depreciation of those slaves, in addition to which, by allowing a greater number of inhabitants, the sources of infection multiply.40

The hygienist also drew attention to the kitchens located in the attics of the houses, which were generally dark and had small spaces, plus the inconvenience of smoke, pointing out that this contributed to the high mortality rate of slaves. As well as recommending that the Recife City Council should not approve any more buildings of the standard existing in the city, he also suggested that, in the new standards, the first floor should be raised five to six palms (1.10 m to 1.32 m) above the final level of the land, not allowing landfill with sand from the sea or river without it being washed beforehand.

The incorporation of sanitary measures into ordinances took place during the second half of the 19th century, with new building standards. The Recife City Council’s ordinances, published through provincial laws (LP),41 contain provisions on: prohibiting the construction of townhouses with more than two floors (LP n. 650/1866); allowing the construction of attics in houses with up to two floors and in houses that were at least 22 palms (4.84 m) high (LP n. 784/1868); detailing the measurements of attics, establishing a minimum height of 13 palms (2.86 m) and providing for their windows (LP n. 797/1868).

Thus, since 1868, Recife’s ordinances, incorporating some of the recommended hygienic measures, set new standards for housing: single‒storey and elevated from the ground, set back and with gardens, or in line with the roads, but elevated from the ground and with side gardens. The standard of the plots was changed to accommodate the width of the houses plus a minimum side setback of 3.30m, which provided direct lighting and ventilation for the rooms.

Since then, the Recife City Council has allowed houses of different shapes and sizes to be built outside the street alignment, as long as the “exterior design” is submitted to it. The guarantee of the plastic form of the buildings gradually gave way to the permission of forms resulting from of buildings with different systems. Houses built to this new standard are becoming viable in the city’s expansion areas, due to new configurations and the size of the plots that are being defined. The designs of the new buildings gradually ceased to be expressed in the text of the law.

According to Reis Filho (1997), the houses with high basements, still facing the street, represent a transition in Brazilian colonial architecture between the sobrado and the single‒storey house. These new standards were formulated as a result of a new moment in Brazilian society, whose dependence on slaves for domestic services began to decline in the second half of the 19th century.

Thus, the structure of the thin, tall sobrado in the center of Recife, which, until the middle of that century, imposed a use of the dwelling based on the presence and even the abundance of slaves ‒ to supply the kitchen on the top floor; to remove the sewage barrels (the tigers); to dispose of household waste etc. ‒ slowly changed from the third quarter of the 19th century onwards, with the elimination of slave labor, the development of paid work and the improvement of construction techniques.

At the end of the 19th century, Recife, already equipped with water and sewage, using imported equipment, saw the emergence of urban houses with new layouts, away from the neighbors and with side windows. The trend became more widespread, albeit slowly, with larger portions of space between buildings, and the detached house within the plot came to characterize the city’s suburbs.

The Proclamation of the Republic, which put an end to the Brazilian Empire, brought with it a new legal order and a new urban planning system, in which some aspects that stemmed from the imperial period were initially consolidated, but new standards were also drawn up which, over the course of the 20th century, replaced those that had been in place until then. Municipal ordinances changed their name, based on the modernization of legislative technique, but their form and content remained the same in the early days of the Republic. In the republican regime, the term “municipal ordinances” was replaced by “municipal laws, municipal decrees” and others, in the exact sense of the word and under the terms of modern legislative technique.

In the urban sphere, specifically, permanence and change coexisted until the middle of the new century, when the modern movement began to express itself more clearly in municipal regulations on the construction of urban space. The laws of the early republican period gradually added hygienic principles, based on a new medical conception, due to advances in bacteriology and microbiology that questioned the traditional knowledge that had been in force until then, based on the theory of miasmas. New urban planning principles also developed alongside hygienic precepts, and came to characterize Recife’s urban planning laws in the first half of the 20th century. Gradually, these laws erased the Portuguese memory enshrined in municipal ordinances, giving way to the principles of the modern movement.

The dynamics of the social process and the expansion of the city through new subdivisions gradually made the relationships established more complex, which led to a trend towards the specialization of urban planning laws. Some matters, which were then consolidated in municipal codes of bylaws, gradually became matters for other branches of legislation and other regulatory bodies, while, throughout the 20th century, urban planning laws became more and more specific in the form of land subdivision laws, land use and occupation laws, building and facilities laws and other laws on specific topics, which were exceptions to the general laws, such as laws governing historical heritage, environmental heritage and those relating to Special Zones of Social Interest.

Final considerations

With the aim of demonstrating the importance of documentary research in archives, this article concludes by emphasizing the research process. It highlights the need to search for different types of historical records, in different collections, in order to gather the key elements that make the history of imperial Recife intelligible and on which it is based. It expresses the exercise of capturing official written documents produced by public bodies ‒ municipal ordinances ‒ to dismantle them, in order to separate their elements and place them in confrontation with other documents, including those of a different nature, such as photographs of the city, testimonies from visitors, among others. It thus promotes a re‒signification of the documents, adding new layers of meaning to the documentary mass.

By favoring the writing of history with the archive as the object and the document (in its diversity of formats) as the basic source, the narrative constructed here takes into account what Le Goff (1990, p. 466) states: “One must take the word ‘document’ in the broadest sense, a document written, illustrated, transmitted by sound, image, or in any other way.”

The history of imperial Recife, written from documentary sources, with the support of a historiography of reference, made it possible to identify important historical elements, not only of Recife, but also of Brazil. It notes the enshrinement of Portuguese memory in the country’s legal framework, when Brazil became an independent nation from Portugal, demonstrating the inertia of the traditions of formal processes and customs, and revealing the extensiveness of this process to other Brazilian cities. It clearly defines temporal milestones in the legislative processes at local level, when it demonstrates changes in the predominant concerns in the rules that regulate the city’s buildings, whose aesthetic emphasis gives way to a hygienist emphasis.

In this process, the historical document was conceived as the result of an assembly, conscious or unconscious, of the society that produced it, the effects of which were maintained in subsequent eras. We took into account what Le Goff (1990, p. 470) says: “A document is not just any document It is a product of the society that made it according to the relations of forces that held power there”.

Considering this perspective and also based on Foucault (1972), who points to the need to demystify the apparent meaning of the document, we conclude that Recife’s municipal codes of bylaws, by providing support for the exercise of municipal economic police power ‒ police in the sense of civility, and economic in the sense of good administration ‒ are authentic civics manuals which, as well as dictating legal rules to citizens, teach them how to conduct themselves in the community, with a view to the common interests of tranquillity, safety and public health. As instruments of the municipality’s exercise of power, they do not, however, exclude the constraint and limitation of various interests. As Foucault (1977) shows, their disciplinary content has a positive and constructive aspect, due to the civilizing nature they represent, imposing social, aesthetic and hygienic behaviour.

In reconstructing this relatively distant past, the written document of the postures of imperial Recife was irreplaceable. It reveals traces of the City Council’s normative activity, as a testimony to these activities that took place in the past. In this way, it adds the dimension of time to the understanding of the concepts in force, the knowledge in force at the time and current behaviors, mentalities and practices. It expresses society’s stage of development, revealing aspects that Santos (1996) considers to be the technical means capable of making the abstract concepts of space and time empirical.

By providing a reflection on a section of the documentary collection researched, the historical narrative of imperial Recife exposes the conflicts that permeate these laws in a period characterized by major changes: in the context of the city, this period portrays a phase of population growth in Recife, without the necessary infrastructure to support it, which leads the municipal management to face various problems in providing sanitary conditions for the city; in the context of management, the period characterizes the transition between the tradition of colonial management, subject to the Portuguese Crown, and the autonomy of local urban management; and in the field of architecture and urbanism, the period signals the end of times in which both disciplines walked together, through the principles of urban composition ‒ the central axis of the classical approach ‒ which were replaced in the 20th century by abstract urban parameters ‒ typical of the modern approach ‒ which abandoned the design of the city.

References

BRASIL. Constituições do Brasil. Brasília: Editora do Senado Federal, 1996.

BRAUDEL, Fernand. Histoire et sciences sociales: la longue durée. Annales ESC, Lisboa, Editorial Presença, n. 4, oct.‒déc. 1958.

CHOAY, Francoise. A regra e o modelo. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1985.

CORBIN, Alain. Saberes e odores. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1987.

CORTINES LAXE, João Baptista. Regimento das câmaras municipais ou lei de 1º de outubro de 1828. 2. ed. Corrigida e aumentada por A. J. Macedo Soares. Rio de Janeiro: Garnier, 1885.

FERREZ, Gilberto. Raras e preciosas vistas e panoramas do Recife, 1755‒1855. Recife: Fundarpe, 1984.

FERREZ, Gilberto. O álbum de Luiz Schlappriz: memória de Pernambuco. Álbum para os amigos das artes, 1863. Recife: Fundação de Cultura da Cidade do Recife, 1981.

FERREZ, Gilberto. Álbum de Pernambuco e seus arrabaldes. Litographia de F. H. Carls. Recife: Prefeitura Municipal do Recife, 1956.

FOUCAULT, Michel. Microfísica do poder. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal, 1979.

FOUCAULT, Michel. Vigiar e punir: história da violência nas prisões. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1977.

FOUCAULT, Michel. A arqueologia do saber. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1972.

FUNDAÇÃO CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN. Ordenações afonsinas, manuelinas e filipinas. 2. ed. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1998. Livros I a V.

KIDDER, Daniel P. Reminiscências de viagens e permanências no Brasil (províncias do Norte). São Paulo: Livraria Martins Fontes, 1943.

KOSTER, Henry. Viagens ao Nordeste do Brasil. Recife: Secretaria de Educação e Cultura do Estado de Pernambuco, 1978.

LANGHANS, Franz‒Paul. As posturas. Lisboa: Tipografia da Empresa Nacional de Publicidade, 1937.

LE GOFF, Jacques. História e memória. Campinas: Editora Unicamp, 1990.

MACHADO, Roberto. A da(n)ação da norma: medicina social e constituição da psiquiatria no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal, 1982.

MACHADO, Roberto. Ciência e saber: a trajetória da arqueologia de Foucault. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal, 1981.

MARX, Murillo. Cidade no Brasil: terra de quem? São Paulo: Livraria Nobel; Edusp, 1991.

MELLO, José Antônio Gonçalves de. Nobres e mascates na Câmara do Recife, 1713‒1738. Revista do Instituto Arqueológico, Histórico e Geográfico Pernambucano, Recife, v. L, 1981.

MENEZES, José Luiz M. et al. Uso e ocupação do solo: Recife − uma visão retrospectiva. Jornal do CREA, Recife, maio‒jun. 1995.

PEREIRA DA COSTA, Francisco Augusto. Anais Pernambucanos. Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual, 1966. (10 volumes).

REIS FILHO, Nestor Goulart. Quadro da arquitetura no Brasil. 8. ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1997.

ROLNIK, Raquel. A cidade e a lei. São Paulo: Fapesp; Studio Nobel, 1997.

SALGADO, Graça (coord.). Fiscais e meirinhos: a administração no Brasil colonial. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional; Nova Fronteira, 1985.

SANTOS, Milton. A natureza do espaço: espaço e tempo − razão e emoção. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1996.

SODRÉ, Nelson Werneck. Síntese de história da cultura brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1970.

SOUZA, Maria Ângela de Almeida. Posturas do Recife imperial. 2002. 312 p. Tese (Doutorado em História) − Programa de Pós‒Graduação em História, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, 2002. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufpe.br/bitstream/123456789/7277/1/arquivo7620_1.pdf.

TOLLENARE, Louis‒François. Notas dominicais. Recife: Secretaria de Educação e Cultura do Estado de Pernambuco, 1978.

VALENTE, Waldemar. Maria Graham: uma inglesa em Pernambuco nos começos do século XIX. Recife: Coleção Concórdia, 1957.

VAUTHIER, Louis. Casa de Residência no Brasil. Revista do SPHAN, Rio de Janeiro, n. 7, 1943. Tradução de Vera Mello Franco de Andrade.

ZANCHETI, Sílvio M. O Estado e a cidade do Recife (1836‒1889). 1989. 286 p. Tese (Doutorado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) – Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), 1989.

ZENHA, Edmundo. O município no Brasil (1532‒1700). São Paulo: Instituto Progresso Editorial, 1948.

Received on February 28, 2023

Approved on July 19, 2023

1 The article is based on the author’s doctoral thesis and the research on which it was based (Souza, 2002).

2 Prefeitura Municipal do Recife. Papéis antigos. Arquivos. Nova Série. Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje). Recife: PMR, n. 1, p. 47, Dec. 1976 (emphasis added).

3 Província de Pernambuco. Coleção de leis, decretos e resoluções da província de Pernambuco (1835‒1889). Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emereciano (Apeje).

4 The Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emereciano (Apeje) was founded in 1945 and its name pays homage to the man who fought for the creation of a body to be the guardian of Pernambuco’s political and administrative memory, having been the archive’s manager for its first three decades.

5 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco. Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, 1814‒1889.

6 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Manuscritos: Actas de Vereação da Câmara Municipal do Recife. Recife: Instituto Arqueológico Histórico e Geográfico de Pernambuco, Livros: 3 (1773‒1777), 6 (1821‒1828) e 7 (1829‒1832).

7 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco. Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, Recife: Livro 8, 12/8/1830, p. 25‒25 verso.

8 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Posturas adicionais da arquitetura, regularidade, e aformoseamento da cidade. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco. Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, Recife: Livro 18, 12/10/1839, p. 60‒64 verso.

9 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Posturas adicionais polícia das ruas. Art. 3º. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara Municipal do Recife ao Presidente da Província. Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal. Livro 18, 25/11/1839, p. 71 a 76 verso.

10 Diario de Pernambuco, n. 475, de 13/9/1830, p. 3.122; n. 478 de 16/9/1830, p. 3.133; n. 527, de 17/11/1830, p. 3.334‒3.335. Recife, Microfilme. Fundação Joaquim Nabuco.

11 Diario de Pernambuco, n. 167, de 5/8/1831, p. 680; n. 173, de 13/8/1831, p. 705‒706; n. 176, de 18/8/1831, p. 717; n. 182, de 26/8/1831, p. 741‒742; n. 248, de 22/11/1831, p. 1.005‒1.007; n. 261, de 9/12/1831, p. 1.059‒1.060; n. 262, de 10/12/1831, p. 1.063‒1.064; n. 264, de 13/12/1831, p. 1.072; n. 265, de 14/12/1831, p. 1.075; n. 266, de 15/12/1831, p. 1.079; n. 270, de 20/12/1831, p. 1.093; n. 272, de 23/12/1831, p. 1.101; n. 274, de 29/12/1831, p. 1.102‒1.103; n. 276, de 2/1/1832, p. 1.121‒1.122; n. 277, de 3/1/1832, p. 1.125‒1.127. Recife, Microfilme. Fundação Joaquim Nabuco.

12 Província de Pernambuco. Manuscritos: Anais da Assembleia Provincial. Recife: Assembleia Legislativa de Pernambuco, 1835‒1889.

13 Província de Pernambuco. Relatórios dos Governadores de Província enviados à Assembleia Legislativa. Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje). Recife: Typografia de M. F. de Faria. 1835‒1889.

14 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco. Recife, Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, 1814‒1889.

15 According to Mello (1981, p. 255), the category of “village” was attributed to those urban centers that were located in territory belonging to the grantee and not to the Crown. This was the case of Olinda (1537) and, later, Recife (1710). All Brazilian cities prior to the 18th century were officially founded in Crown territories: Salvador (1549), Rio de Janeiro (1565), São Luiz (1612) and Belém (1616).

16 Due to the importance of article 66 of the 1828 law in defining the content of the ordinances to be established by the councils of Brazilian municipalities in the imperial period, we have chosen to present it in its entirety.

17 Article 15 of the Lisbon Code of 1886 apud Langhans, 1937, p. 304.

18 Rio de Janeiro. Câmara Municipal. Posturas da Câmara Municipal do Rio de Janeiro. Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Imperial e Nacional, 1830, p. 20.

19 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Posturas adicionais polícia das ruas. Art. 3º. In: Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara Municipal do Recife ao Presidente da Província. Recife: Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, livro 18, 25 de novembro de 1839, p. 71‒76 verso.

20 Articles 44 and 45 of the Pompilhosa da Serra Code of 1868 apud Langhans, 1937, p. 311.

21 Rio de Janeiro. Câmara Municipal. Posturas da Câmara Municipal do Rio de Janeiro. Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Imperial e Nacional, 1830, p. 22.

22 Diario de Pernambuco, n. 170, 3.8.1849, p. 2; n. 171, 4.8.1849, p. 1‒2. Recife, Microfilms. Fundação Joaquim Nabuco.

23 Published in 15 editions of Diario de Pernambuco: n. 167, 173, 176, 182, 248, 261, 262, 264, 265, 266, 270, 272, 274, 276 and 277. Recife, Microfilms. Fundação Joaquim Nabuco, Aug. 1831 to Jan. 1832.

24 Data based on estimates presented by Menezes et al. (1995, p. 1) for the year 1848, and by Zancheti (1989, p. 136) for the year 1872.

25 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco. Recife, Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, livro 8, 12.8.1830, p. 25‒25 verso.

26 The term “toecaps” refers to the edge of the roof that extends beyond the façade line of the building, with or without the protection of gutters to collect rainwater.

27 The term “platband” refers to the upper part of a building’s façade that conceals the roof. It can be either the façade wall itself that rises, or a bulkhead located beyond the façade line.

28 The term “cornice” refers to a band with projections, usually horizontal ribs, which stands out horizontally from the platband, or the upper part of the wall of a building.

29 Diario de Pernambuco, n. 527, of 17.11.1830, p. 3.334‒3.335. Recife, Microfilm. Fundação Joaquim Nabuco.

30 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Posturas adicionais da arquitetura, regularidade, e aformoseamento da cidade. Manuscritos: Correspondência da Câmara do Recife ao Presidente da Província de Pernambuco. Recife, Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emerenciano (Apeje), Série CM – Câmara Municipal, livro 18, 12.10.1839, p. 60‒64 verso.

31 In this summary, it was considered essential to present the central content of the architectural composition rules established for Recife’s sobrados, in order to demonstrate the level of refinement and detail of these rules.

32 In order to enable “the regularity and shaping” of the city, as stated in the title of the Posturas, the the Recife City Council is responsible for tasks such as providing the molds for the cornices, which are gradually replacing the heavy handmade cornices.

33 The term “cordons” refers to a protrusion, usually with a half‒circle cut section, arranged horizontally on the façades of buildings indicating the height of the threshold at floor level, or in other places for decorative purposes.

34 Recife. Câmara Municipal. Posturas adicionais da arquitetura, regularidade, e aformoseamento da cidade, op. cit.

35 Comissão de Higiene Pública. Bases para um plano geral de edificações da cidade. Microfilme. Diario de Pernambuco, Recife, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco (Fundaj), 28/8/1855, p. 2 (emphasis added).

36 Pernambuco. Província. Coleção de leis, decretos e resoluções da província de Pernambuco. Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emereciano (Apeje). Recife: Typografia de M. F. de Faria, 1835‒1889.

37 In 1858, the French engineer Luiz Cambrone signed a contract with the provincial government to implement sewage and urban cleaning works and services in Recife.

38 Comissão de Higiene Pública. Bases para um plano geral de edificações da cidade, op. cit., p. 2.

39 Comissão de Higiene Pública. Bases para um Plano Geral de Edificações da Cidade, op. cit.

40 Idem.

41 Pernambuco. Província. Coleção de leis, decretos e resoluções da província de Pernambuco. Arquivo Público Estadual Jordão Emereciano (Apeje). Recife, Typografia de M. F. de Faria, 1835‒1889.

Esta obra está licenciada com uma licença Creative Commons Atribuição 4.0 Internacional.