Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 36, n. 3, Sept./Dec. 2023

The archive as an object: written culture, power and memory | Thematic dossier

The paper in the captaincy of Minas Gerais

Identification of provenance from the material study of the separate documentation of the Casa dos Contos collection of the Arquivo Público Mineiro (1750-1800)

El papel en la capitanía de Minas Gerais: identificación de procedencia a partir del estudio material de la documentación separada del fondo Casa dos Contos del Arquivo Público Mineiro (1750-1800) / O papel na capitania de Minas Gerais: identificação de proveniência a partir do estudo material da documentação avulsa da coleção Casa dos Contos do Arquivo Público Mineiro (1750-1800)

Marina Furtado Gonçalves

PhD in Social History of Culture from the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Professor on the Bachelor’s degree in Museology at the Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Brasil.

Abstract

Paper is considered a material element of culture and must be studied in its materiality and historicity. This research sought to identify the manufacturers of paper used by the public administration in the captaincy of Minas Gerais, understanding the origin of the paper from material and historical analyzes in an interdisciplinary perspective, highlighting the Italian papers. The characterization of the documentation aims to contribute to the study of the archive as a material object of culture.

Keywords: rag paper; watermarks; Casa dos Contos collection; XVIII century.

Resumen

El papel es considerado un elemento material de la cultura y debe ser estudiado en su materialidad e historicidad. Esta investigación buscó identificar los fabricantes de papel utilizados por la administración pública en la capitanía de Minas Gerais, comprendiendo el origen del papel a partir de análisis materiales e históricos en una perspectiva interdisciplinaria, destacando los papeles italianos. La caracterización de la documentación pretende contribuir al estudio del archivo como objeto material de la cultura.

Palabras clave: papel de trapo; marcas de agua; colección Casa dos Contos; siglo XVIII.

Resumo

O papel é considerado um elemento material da cultura e deve ser estudado em sua materialidade e historicidade. Esta pesquisa buscou identificar os fabricantes dos papéis utilizados pela administração pública na capitania de Minas Gerais, compreendendo a proveniência do papel a partir de análises materiais e históricas em uma perspectiva interdisciplinar, destacando os papéis italianos. A caracterização da documentação visa contribuir para o estudo do arquivo como objeto material da cultura.

Palavras-chave: papel de trapo; marcas d’água; coleção Casa dos Contos; século XVIII.

Support and materiality of writing

There is a tendency in the historiography of written culture to dematerialize the act of writing and reading. Most of the works in this field of research are concerned with quantitative data on readers and written works, the teaching of reading and writing, censorship, authors, among others. However, for some decades now, some researchers have focused on the importance of the material act of reading and writing, as not only a reflection, representation or appropriation. McKenzie (1999) argues that texts are not isolated from the material form in which they are presented for reading, that is, the author combines form and content and not only adheres to a traditional methodology, based mainly on written documentation (Roche, 2000). In the same way, Roger Chartier (2002) published several works on the meaning of the forms assumed by writing, with a view to mobilizing material things to understand societies.

Fernando Bouza Álvarez (1998) has discussed the different forms of communication in force in Spain during the 17th century, relating the functionality of orality, visuality and writing to the material forms in which they manifest themselves, including gestures. The author, likewise Marcelo Rede (1996), points to a combination perspective, in which the material and the immaterial must go together, going beyond the simple overlap of information coming from different fields of analysis and inducing their mutual interaction and reciprocal control.

In the field of cultural history, recent research on cultural heritage has been concerned with the inseparability of material and immaterial in the search for understanding traditional ways of doing things, as pointed out by José Newton Coelho Meneses (2015). In the study of paper, as a support for writing, the point of view of Meneses and Bouza Álvarez proves to be very useful, as it raises the understanding of the artifact from its production, use and consumption. These thoughts can be combined with the ideas of Marcelo Rede (1996), when remembering that the physical-chemical properties of objects bring evidence of several stories revealing traditions, knowledge, ways of making objects or goods produced and consumed by societies. Antonio Castillo Gómez (2006) rescues the analytical procedures of paleography to understand how the different kinds of writing fulfill their social function of communication and works with a social history of written culture, focusing on the study of production, diffusion, use and conservation of objects, supported by discourse, practices and representations, that is, a segment of the physical environment transformed and culturally appropriated by man.

Based on the idea of combining levels of analysis proposed by the study of material elements of culture, the document itself is considered, composed of paper, paints, marks and traces, an object of a material nature historically constituted. Not only do the inked contents of documents provide us with historical, social, artistic and cultural information: the study of the support – in this case, paper – can help to reveal complex issues beyond the written and painted content of the manuscript. In the material structure of paper, especially those made manually, there are characteristics that testify to the production methods inserted in their historical context and “like the text itself, it expresses attitudes, thoughts and symbologies specific to each era and society” (Almada, 2010, p. 40).

Between the 15th and 17th centuries, European culture went through a process of written evolution, without, however, abandoning the oral and iconic-visual tradition. For nobles, mainly, the use of written form guaranteed the maintenance of the power and social functions of the nobility, allowing better administration of their own houses, since it was possible to record rules, accounts, requests, among others in a more effective way, perpetuating information that could serve as future proof. In this way, writing promoted cultural centralization, based on maintenance for economic development, gaining strength in the dissemination of information and ideas (Bouza Álvarez, 1997). Written documents gained so much prominence in the society of modern monarchical states that many documents were destroyed, aiming to erase some event, memories or ideologies. Bouza Álvarez states that “whoever wanted to erase the memory of something knew that they had to destroy the written records to avoid evidence, memory, fame or simple constancy” (Bouza Álvarez, 1997, p. 33), reinforcing the importance of what was written and kept.

In the same period, with European maritime expansion and the consequent need for the administration of overseas domains, modern monarchies began to make extensive use of written documentation as one of the mechanisms used to maintain power. Colonial relations were maintained with written words. They allowed and granted mobility to the practices of governing from a distance. For institutions of power, writing was a systematic and indispensable means of information, as it contributed to the centralization and effective control of the State (Bellotto, 2014), as well as to the affirmation of the sovereignty of the king and the its administration.

Writing was a vehicle of information, a control mechanism, therefore, an instrument of remote governance (Conceição, 2013). However, at a time when the Atlantic crossing took almost three months, political and administrative errors and distortions were made due to “administrative time”, relating to the legal processing of documents circulating between the metropolis and colonies, resulting in the delegation of authority and autonomy of governments in the peripheral areas of the empires. It was necessary to ensure that an effective administration prevailed and “Portugal used the most efficient administrative, fiscal and military instruments to guarantee not only geopolitical, but also political, in America” (Bellotto, 2014, p. 393). Therefore, the production of documents intensified and generated a diverse series of document kinds and typologies, such as correspondence, economic maps, royal edicts, receipts, copies of monarchical legislation, among others.

In the Iberian world, the subsequent contact with other territories, the expansion and military, political and economic dominance that generated the continuous traffic of people circulating with objects, goods and beliefs provided the accumulation of new knowledge and new information dependent on writing to become effective. Dom João V, in order to project Portugal as an international power, believed that it was necessary to invest in the cultural area, of letters, of books, being responsible for the construction, for example, of the Joanina Library at the University of Coimbra, also increasing the university’s funding for the purchase of books. In the same way, Dom João V used literary production, especially in the areas of history, geography and Portuguese language, to affirm Portugal as a great nation, investing in publications of reference books for research such as Vocabulario portuguez e latino, authored by Rafael Bluteau, Nova escola para aprender a ler, escrever e contar, by Manuel de Andrade de Figueiredo and Historia genealogica da Casa Real Portugueza, by Dom António Caetano de Souza, the latter developed by the Royal Academy of History. The academy, founded in 1720, contributed to studies of the historical-geographical description of Portugal and its domains, as well as other subjects of Portuguese interest.

Already in the second half of the 18th century, with the encouragement of the Portuguese Crown to seek the renewal of knowledge, an information network was formed allowing the “18th century Portuguese State to know in a more in-depth and precise way its domains in Europe, Asia, Africa and, above all, in America, that is, recognizing the physical limits of this sovereignty” (Domingues, 2001, p. 824). During this period, several naturalists, engineers, cartographers, among other specialists, made scientific trips to the colonies, specifically to Brazil, and produced memoirs, essays, letters, catalogs and reports, as well as administrative speeches sent to the Crown. In addition to the documentation developed on paper ‒ not only writing, but also maps, drawings and paintings ‒, the researchers also sent plant, animal and mineral samples, contributing to knowledge of the territory, natural species and economic potential.

With the development of knowledge about the empire and its obvious economic repercussions, especially in agricultural, mineralogical and industrial activities, it was necessary to increase the dissemination of information, mainly among the elites, “in order to teach and encourage subjects to participate in the economy of the kingdom in a dynamic, rational and productive way, through the use of new products and techniques” (Domingues, 2001, p. 829). This dissemination was done through manuscripts and printed matter, books and leaflets, reflecting the relevance of the use of writing, and the consequent use of paper, to promote not only technical-scientific advancement, but also to guarantee the control of information, since they were published by printers working for the Crown, as pointed out by Nunes and Brigola (1999).

Writing thus became an essential mechanism for the maintenance of modern monarchies, covering economic, social, cultural and political spheres. The accumulation of documentation relating to all areas of administration, a reflection of the installed bureaucracy, resulted in the creation of the great archives of the High Modern Age, due to the premise of the need to “know in order to act, and, once the decision was adopted, it was necessary to disseminate and explain to achieve success” (Bouza Álvarez, 1997, p. 87). In addition to the idea of a place destined to preserve memory for posterity, the archive arises from a utilitarian concept, seeking bureaucratic centralization and highlighting the proof nature of documents. The primary function of the archives was (and still is) to collect and process documents after fulfilling the reasons for which they were generated, a large part of which was produced by the Crown’s own administrative machinery.

With the massive use of writing in government bureaucratic bodies, especially following the introduction of written consultation and navigation, the volume of paper since the beginning of the Modern Age has become significant, generating not only the need to manage it in archives and libraries, but also to conserve it. In the same way, the growing amount of paper also occurred in private spaces, gaining significant importance, until then not so valued by the nobility. The progressive production of material traces converged on the problem of preserving papers, making it necessary to conserve support and information (Conceição, 2013).

The materiality of such documents reveals information that may go unnoticed by researchers. However, “if questioned with methodological propriety, the material traces in documents can be the way to reach answers that perhaps could not be reached by other means” (Almada, 2014, p. 137). In order to understand documents as material objects of culture in an interdisciplinary analysis perspective, especially regarding their provenance, we proposed the study of the administrative documentation of the captaincy of Minas Gerais in the second half of the 18th century. The captaincy’s documentation was chosen due to the ease of access to a significant corpus of documents, such as the Casa dos Contos collection, under the custody of the Arquivo Público Mineiro [Public Archive of Minas Gerais]. This collection went through the process of identification, microfilming and packaging and did not receive conservation-restoration treatments, such as small repairs, flattening, deacidification, care to stabilize metalloacid paint, and others. In this way, the documents maintained their material characteristics, as well as the marks of use, allowing the proposed analyses.

The widespread use of text as a form of administrative communication also boosted the production and circulation of materials necessary for writing. Some of them, such as furniture and writing inks, did not require laborious production technology (Segredos, 1794; Figueiredo, 1722), unlike paper, which depended upon a large space to house all stages of manufacturing, large volume of water, raw material not abundant, and in-depth knowledge of techniques for producing quality paper.

Making paper

As it is known today, paper dates back to 2nd century China, preceding the “Arab era” that began in the year 751, in the context of the battle of Talas, in present-day Uzbekistan, in which the Arabs defeated the Chinese army, making prisoners some soldiers who would have transmitted the knowledge of the paper manufacturing process (Balmaceda, 2002). In the 13th century, the “European era” of paper production began, centered in Fabriano, Italy. The differentiation between the Arabic and the Italian production techniques was mainly due to the use of a hydraulic mill to crush the fibers with hammers covered in metal parts at their ends, guaranteeing a finer and more homogeneous pulp, “revolutionizing the grinding and the trampling of the cloth” (Gimpel, 1977). Furthermore, the use of starch was replaced by meat glue in sizing, as starch contributed to the deterioration of the paper (Sabbatini, 1988).

From the 15th century onwards, France was self-sufficient in paper production, asserting itself with a product of excellent quality. The culture of papermaking then spread towards Germany and Switzerland and then to England, Poland, Holland, Russia and Scandinavian countries (Hunter, 1978).

Paper, used for handwritten or printed texts until the beginning of the 19th century, was made from rags of fabric usually made from cotton, linen or hemp. Paper mills were always installed next to the bed of a river or stream, as they needed water as a driving force and to prepare the pulp. Rag paste was the first material used to make paper, in which fabric remains were subjected to maceration and fermentation. The rags, placed in stone containers with the addition of water, were softened manually and could be beaten with hammers powered by hydraulic force, separating the fibers. The process lasted from five to thirty days and, as it was a hard and painful procedure, it was necessary to modernize production (Hunter, 1978). In 1680, the use of the “Dutch machine” began, a machine developed to decompose the fibers of rags that produced, in four or five hours, the same amount of rag pulp that an old hammer mill with five stones produced in 24 hours.

The paste obtained by dispersing the fibers was distributed over molds to shape the sheets. The molds, consisting of a frame in which several parallel wires were fixed, forming a kind of sieve, allowed the elimination of excess water from the pulp. The paper folio1 was produced manually, by immersing the mold in the container with the dispersed pulp, in precise movements for a homogeneous distribution of the fibers. Handling was done using the removable frames, avoiding hand contact with the folio in formation. Then, the movable frame was removed and the sheet of paper was placed, one by one, on felts, which were then stacked and pressed, in order to eliminate excess water. After drying, the folios were sized with the help of a brush or by immersion, dried on clotheslines and pressed again.

Making a sheet of rag paper was a demanding operation involving great skill and absolute precision and, even with a simple and repetitive gesture, six to seven years of work were required to achieve perfection. The lives of the owners of the large mills, administrators, master papermakers and workers revolved around the factory, where they worked and lived, giving rise to a “community within the community”, keeping the secret of the craft enclosed within the walls of the mills. Believing in the formed community and believing they differentiated themselves from a backward socio-cultural context, the mill owners often distinguished themselves in local political and administrative life (Sabbatini, 1988).

The watermarks

During the production process, it was possible to print watermarks on the paper which, as well as the distances of points and bends, could identify the manufacturer, guaranteeing authenticity. The watermark design was formed from a figure molded in brass that was later intertwined with the mesh threads of the molds, like embroidery. The small brass sculptures normally represented coats of arms, symbols related to royalty and elements of nature. The watermark commonly occupied half of the folio, in the longitudinal direction, and, when the rag paper paste was deposited on the mold, in these places, a smaller amount of the mixture was concentrated, creating more transparency, making the drawings visible, especially when observed against the light. Since then, a sheet of paper has become, in itself, a source of knowledge, telling its own story, based on the messages embedded in it in the form of almost hidden impressions: the watermarks.

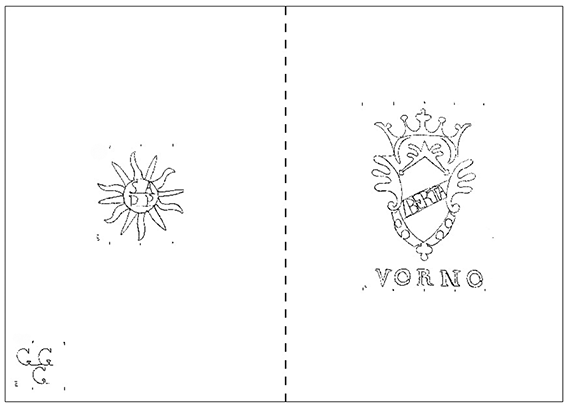

During the 16th century, paper producers also began to use the countermark, generally located on the other half of the folio, in symmetry with the main watermark, hence the name “countermark”. Constituting a confirmation of the manufacturer’s identity, this secondary mark normally contained only initials and, over time, began to include the name of the manufacturer or factory, the location, the year of manufacture and simple decorative figures. Smaller corner countermarks could also be observed, commonly located at the bottom and/or top corner of the sheet of paper, featuring monograms, isolated letters, numbers and small symbols (Figure 1). These marks, as pointed out by Heawood (1950), were used by the Genoese on papers exported to Spain and Portugal, since the end of the 17th century.

Figure 1 ‒ Scheme of the distribution of marks in document 324: main countermark (on the left), countermark corner mark (bottom left edge) and watermark (right). Source: APM, CC, cx. 29, pl. 10,584, doc. 4

Also as secondary, there are complementary watermarks, those represented on both sides of the sheet of paper, whose contents complement each other, as well as the bull and the bullfighter. Likewise, there are multiple marks, normally small, profusely repeated on the sheet of paper (Santos, 2015). Although there are several types of marks, it is more common to observe in 18th century papers a greater presence of watermarks, countermarks and complementary watermarks.

The right to use a watermark, in the 14th century, was granted after payment of a fee, and the insertion of initials of paper manufacturers or merchants on the folios demonstrated power and social status. In France, in 1582, an order from Henry III imposed the use of the countermark on the other half of the sheet, in symmetry with the main watermark, containing the initials of the paper manufacturers. In 1675, in Voltri, in the province of Genoa, Italy, twenty influential paper merchants added their initials to the papers produced in the region (Balmaceda, 2016).

By observing the sheet of rag paper against the light, it is possible to easily identify these elements. In this way, the researcher can interrogate the document created on such a support to uncover issues, as is the case in this study, whose intention is to indicate the provenance of the folios used by the public administration in the captaincy of Minas Gerais.

Paper in the captaincy of Minas Gerais

In Portugal, the oldest paper mill was established in Leiria, authorized by royal letter from Dom João I, dated 1411. During the 18th century, several factories were installed in Portuguese territory, but the country was unable to meet the internal demand or that of its colonies, having to import paper from other nations, especially Italy and Holland, for a long time major producers of rag paper. In the 18th century, for the captaincy of Minas Gerais, this fact can be noted, for example, in the works of Gonçalves (2013), who brought together Italian watermarks, and Costa (2016), who listed Italian, Dutch and just a Portuguese one.

Since the first official Brazilian paper factory was only implemented in 1809 (Almeida; Hannesch, 2019), the hypothesis is that all the folios used to write the Minas Gerais administrative documentation circulating in the second half of the 18th century were from European origin. However, the possibility of clandestine paper production in Portuguese America is not excluded.

The social moment of paper consumption as a commodity finds few sources in Brazil and the world. Daniel Bellingradt, a paper scholar, highlights the lack of studies on the world paper trade in the Modern Era. According to the author,

paper historians have not paid much attention to the trade of the material; economic and trade historians have not been interested in paper at all; and book historians sometimes mention the connection of paper production and its selling to the world of printing, but tend to eschew the details linking trade activities. (Bellingradt, 2014, p. 117-118)

Although the lack of bibliographical sources is an obstacle to research, from the perspective of the history of material culture, the artifact itself can be studied to uncover questions. We often take artifacts as peaceful spots, that is, naturalized before our eyes, without realizing their potential. Archive documents are treated here as artifacts, and not only because of their proximity to the text or their framing of the textual reading methods that qualify their uses. They are not a “second-rate document”, incomplete and limited, when compared to the written source, and “it is necessary to invest in understanding this mutable chain to incorporate material culture in its documentary plenitude” (Miller, 2013, p. 276).

Based on this approach, to understand the provenance of the paper used in administrative documentation in the captaincy of Minas Gerais in the second half of the 18th century, the paper itself was used. Thus, we sought to understand history based on the artifact itself, however, without disregarding other sources, raising questions to think about social man and the elements he builds in his experience (Meneses, 2017).2

Methodological procedures

As the object of study, we chose separate administrative documents selected from the Casa dos Contos collection of the Arquivo Público Mineiro [Public Archive of Minas Gerais]. The collection includes handwritten documents linked to public administration from the 18th and 19th centuries (from 1700 to 1853), as well as personal documentation such as letters and certificates, presented in separate and bound documents. It is among the main documentary collections in Brazil and, currently, the documents from Casa dos Contos are held in three institutions: at the Arquivo Nacional [Brazil´s National Archives] and the Biblioteca Nacional [Brazil´s National Library], in the city of Rio de Janeiro, and at the Arquivo Público Mineiro [Public Archive of Minas Gerais], in Belo Horizonte. The name of the collection alludes to the Regimento dos Contos, the body responsible for fiscal control of the kingdom of Portugal between the years 1650 and 1761, but it includes documents from the Junta da Real Fazenda da Capitania de Minas Gerais, whose function was to enforce the metropolitan treasury requirements and standards. These bodies accumulated documents relating to the organization of space, administration, tax collection, among many other manuscripts of interest to the Portuguese Crown. Later, documents from the Finance Treasury of the Province of Minas Gerais and personal documents from the contractor João Rodrigues de Macedo were incorporated.

The collection was selected because it was completely inventoried, microfilmed and stored, without, however, having undergone any conservation-restoration intervention that would alter the material composition of the support or remove signs of use (Gonçalves, 2013). The Casa dos Contos collection is made up of 55.33 textual linear meters and the selection of documents was made from the Inventory of the Casa dos Contos collection of the Arquivo Público Mineiro [Public Archive of Minas Gerais] (unbound documents),3 in a Microsoft Excel software table, with revision in 2007, made available by the Permanent Archives Directorate. The inventory informs the box number, microfilm roll, microfilming sheet, document number, date, location, title/description of the document contents, descriptors and notes.

Minas Gerais documents dated between the years 1750 and 1800 were pre-selected, totaling 8,914 documents. Those without a date were also considered, as they could be part of the time frame of this research. It was decided to separate the documentation by decades so as not to have a concentration of documents belonging to one year or another. Documentation dated 1800, as well as undated documentation, were considered in two distinct groups.

Among the pre-selected universe, we carried out a simple random sampling, that is, one in which all elements have the same probability of being selected. After applying the sample calculation, 697 documents were totaled. Next, we carried out a convenience sampling,4 in which the choice of documents for analysis considers the different kinds of documents, such as letters, receipts, orders and lists, without favoring one kind of document or another.

After the final selection of documents, we filled out an identification table, based on the proposal of the International Standard for Registration of Paper With or Without Watermarks, developed by the International Association of Paper Historians (IPH), and began registering the watermarks. There are several techniques for recording watermarks present on paper, such as direct photography, with reverse light, with ultraviolet fluorescence, with Dylux paper, by copying, by friction, electroradiography, x-ray radiography and beta-graphy. However “the choice of a technique depends on three factors: availability of the technique, type of material to be analyzed and the objective to be achieved with the study” (Figueiredo Junior, 2012, p. 203). For this research, we opted for photography with reverse light and copying on tracing paper, accessible techniques, without damaging the support, which provide the necessary information.

In a dark room provided by the Archive, we carried out scientific image documentation of each document with direct light, front and back, using the QPcard 1015 gray scale and a paper label with the number of the inventoried object. We then photographed the marks using the flexible light sheet as a reverse light source. Finally, still using reverse light, we placed a sheet of tracing paper over the marks and, using a mechanical pencil with 2B graphite, traced the drawing with minimal pressure on the document. The lines corresponding to the points and bends6 were also recorded in the copy made.

The drawings were scanned and the images (drawings and photographs) received systematic treatment, using a software for this purpose, in order to create an inventory with the watermarks observed. The images were compared with existing databases such as the Bernstein Portal7 and that of the Conservación, Análisis e Historia del Papel (Cahip) study center.8 In addition to electronic repositories, we highlight six bibliographic references that record watermarks of European provenance on papers from the Middle and Modern Ages. The first, entitled “Watermarks in paper in Holland, England, France, etc., in the 17th and 18th centuries and their interconnection”, written by William Algernon Churchill and published in 1935, presents the history of paper production in Holland, England and France, especially between the 17th and 18th centuries, lists paper producers from these countries and registers some watermarks, classifying them for decorative reasons. The next two references, authored by Frans and Theo Laurentius, whose titles are “Watermarks in paper from the South-West of France, 1560-1860” and “Italian watermarks 1750-1860”, list French and Italian manufacturers and marks, respectively.

The book by Maria José Ferreira dos Santos (2015), Marcas de água, séculos XVI-XIX: coleção Tecnicelpa, is the result of the project by the Associação Portuguesa dos Técnicos das Indústrias de Celulose e Papel (Tecnicelpa) to catalog watermarks collected in handwritten documents and printed books in Portuguese libraries and archives. As well as Santos’ work, the cataloging of marks present in Watermarks mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries, authored by Edward Heawood (1950), and in “O papel como elemento de identificação”, by Arnaldo Faria de Ataide e Melo (1926), were quite valid for comparing the watermarks found during the research. Even without an exact reference to the origin of the papers, the two catalogs made it possible to contextualize the observed watermarks in time.

We then analyzed the data from the identification table, grouping the papers with similar characteristics, in order to verify which types of papers were used for the selected documents, their origin and establishing relationships regarding the use of papers and which types of support were privileged.

The provenance of the papers

Among the 697 documents researched, we found a wide variety of watermarks, main and corner countermarks, complementary and multiple marks on 602 papers (86.37% of the total sample). From visual observation of the papers and watermarks documentation, it was possible to create a catalog,9 taking as a reference the registration standard proposed by the International Association of Paper Historians (IPH).

When comparing the inventoried watermarks with the research instruments and other references, we identified the provenance of 562 papers, that is, 93.36% of the documents that presented watermarks. The vast majority are of Italian origin (344 papers), followed by possibly Italian papers (122), Dutch (73), French (21) and one English paper.

For this article, we chose to detail the material characteristics of Italian paper, specifically from the Liguria region. This option is due to the majority of the papers found coming from that location.

Italian paper

The manufacture of paper in Italian territory dates back to the 12th century, initiated by Arab papermakers who took their knowledge to cities such as Amalfi, Genoa, Bologna and also on the island of Sicily, where two paper factories were registered, one of which was close to Palermo and another to Catania (Asunción, 2003) (Figure 2). Among the documents that attest to the beginning of paper manufacturing in Italy, the contract dated June 24, 1235, signed in Genoa, stands out, in which three people, in front of a notary, were appointed to manufacture paper with the clause of not revealing any dictum mysterium. As Sabbatini (2013) points out, this is the oldest European document that proves paper manufacturing.

Figure 2 ‒ Location of the first Italian paper mills, on the current map of Italy. Source: Own elaboration based on the bibliographic information mentioned, 2020. Cartographic base: www.d-maps.com

In the second half of the 13th century, a new type of paper began to appear on the market, “a new paper, very different from the others, a paper that demonstrated finer defibration and a specific consistency, in addition to better receptivity to ink” (Sabbatini, 2013, p. 19). This new product was being developed in the commune of Fabriano, in the province of Ancona, in the Marche region. Fabriano’s paper presented three innovations that contributed to its success in the market: the separation of fibers from rags using hydraulic hammers with metal shoes at their ends, the replacement of starch sizing with animal glue and, finally, the insertion of watermarks on the folios as a certificate of origin and quality. Since then, the paper made in Fabriano has become a status symbol, not only in Italy, but also throughout Europe.

Between the 13th and 14th centuries, Fabriano was a major papermaking hub, exporting not only the “paper” commodity, but also the way of making Fabriano paper. Due to internal competition and the large number of mills installed, many papermakers were forced to leave the commune, taking with them the knowledge of manufacturing quality paper that was already recognized around the world. The dissemination of Fabriano’s way of making paper occurred first in neighboring territories, in Foligno, Urbino and Ascoli Piceno, and then spread beyond the Apennines and the Alps. There are records of master papermakers of Fabrian origin establishing themselves in mills both in the southern portion of Fabriano, in Abruzzo and Campania, and in the northern portion, in the regions of Emilia-Romagna and Veneto (Sabbatini, 2013). The use of mills powered by hydraulic power was already present in Italy in the 13th century, especially for grinding grains and working with metals,10 as rivers with strong currents and waterfall-like stretches favored the installation of this infrastructure (Laurentius; Laurentius, 2018). Therefore, it was only necessary to adapt the mills, causing this kind of production to gradually spread throughout Italy, reinforced by a commitment to exactly make chartam ad usum fabrianensem, that is, paper in the Fabrian way (Rückert; Dietz, 2007).

If in Fabriano the way of making paper was perfected, in Voltri, located about 21 km from the city of Genoa, the structure of the mill building was improved, no longer the result of adjustments to an existing factory, but designed and built for specific use. The Genoese experience represents a break with medieval manufacturing, an adaptation to new market needs that other Italian centers were slow to understand or were not equipped to face. In the mills, equipment was developed, as well as production relations, work organization and commercial mediation (Sabbatini, 1988). Thus, not only were the master papermakers coveted by other regions and nations, but also the “mill carpenter (maestro d’ascia), specialist in the construction of the machines and utensils necessary for production” (Balmaceda, 2002). The mobility of specialized labor then became a concern for the State of Genoa, especially from the beginning of the 14th century, when punitive measures were adopted for the emigration and immigration of these people, with the justification that export knowledge about paper production would be disastrous for its economy.

The increasing development of paper production in the State of Genoa, especially in Voltri, since the beginning of the 16th century, made the physical space suitable for the installation of hydraulic motors next to watercourses, previously occupied by mills dedicated to working with metals, gave way to paper mills, using natural, energy and human resources. In the second half of the 16th century, Voltri was already the most prominent city in the production of writing paper in Europe, with around fifty paper mills. Production growth was exponential until the 18th century, supplying the domestic and foreign markets with papers containing Genoese watermarks (Calegari, 1985).

The coat of arms of the State of Genoa was the inspiration for the creation of several filigrees used to generate watermarks, the most common and widely copied by French manufacturers being the one that presents three circles aligned vertically. The coat of arms of the Republic of Genoa features, in the center, a shield with the red cross of Saint George, patron saint since the 7th century, when Byzantine troops built a church in the city in devotion to him. Flanking the central cross are two griffins, added to the coat of arms in the late Middle Ages. Above the cross there is a crown and, below, a stripe with the words “Libertas”. A variation of Genoa’s coat of arms features the image of the head of the Roman god Janus (Grimal, 2018) above the crown, but this is not always represented. Another variation of the coat of arms, observed since the 15th century, brings the addition of a second shield, placed next to the cross, with a diagonal stripe and the words “Libertas”.

The most complete form of the three circles watermark can be seen from the design present in the document 494,11 which presents, in addition to the circular shapes, the three main elements that are part of the coat of arms: the central cross, the two lateral griffins and the crown in the upper portion. Such elements are also present in the design of document 608, but here the griffins have their heads facing backwards. The variation of Genoa’s coat of arms illustrated above was also used in the design of watermarks, as we noted in document 373, containing the two shields and the crown (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Watermarks that reference Genoa’s coat of arms: a) the marks of the three circles (on the left), b) the griffins with their heads facing backwards (in the center) and c) the variation of the coat of arms with two flags (on the right). Source: APM, CC. a) cx. 56, pl. 30,463, doc. two; b) cx. 81, pl. 20,143, doc. 5; c) cx. 37, pl. 30,099, doc. 5

Another prominent Italian papermaking hub is the Tuscany region, whose beginnings of paper production date back to the 13th century, in a mill in Colonica, south of the commune of Prato. As Sabbatini (1988) points out, paper manufacturing in the region was influenced by neighboring experiences: from Fabriano, at the end of the Middle Ages, and from Liguria, from the 17th century onwards. In Tuscany, three paper production areas stood out: Colle di Val d’Elsa, the Pescia area and the Lucca area, especially in Villa Basilica. Colle di Val d’Elsa, where the Fabrianians traditionally introduced the art of papermaking, represents the pre-Ligurian experience. The regions of Pescia and Lucca were influenced by the Genoese model and developed rapidly from the second half of the 18th century onwards.

Prato’s notoriety was lost to Colle di Val d’Elsa, in the province of Siena, when the manufacture of paper gained strength at the end of the 13th century and beginning of the 14th century. According to Sabbatini (1988), commodity flow rates from 1428 reveal the existence of a dozen paper mills in Colle, placing the Tuscan city among the main Italian paper centers.

The province of Lucca, still the Republic of Lucca, stood out as a producer of writing supports since before the 13th century, with the manufacture of quality parchment. Production was organized and played an important role in the economy, culminating in the creation of the Corporazione dei Cartolai in 1307, a corporation that used the skins of sheep and goats to produce parchment and record books called libri di ragione, used for the administrative control of traders (Toscana, 2020). The production of rag paper in the province only began in 1565 with Vincenzo Busdraghi, in Villa Basilica, reusing the infrastructure of an old mill to manufacture paper and install a printing press. Years earlier, in 1549, Busdraghi opened the first printing house in the province of Lucca and, with a monopoly on the press, asked the General Council for permission to manufacture paper. The council accepts the request and guarantees tax exemption, with the condition of keeping the city supplied with all types of paper and cards for three years (Sabbatini, 2013).

The company formed by Vincenzo Busdraghi, Girolamo, Jacopo, Michele Guinigi and Giuseppe Turchi to manufacture paper was dissolved in 1570, due to difficulties and a lack of experience on the part of the entrepreneurs. The factory then passes to Paolino Vellutelli and then to Alessandro Buonvisi, son of one of the richest and most powerful families in Lucca, who invests in paper production and puts the province, as well as Villa Basilica, in the spotlight in terms of making paper that continues to this day (Sabbatini, 2013). In Villa Basilica, the number of paper mills practically doubled at the end of the 18th century and, at the beginning of the 19th century, paper production involved 20% of resident families (Sabbatini, 1988).

Like the Buonvisi, other noble and wealthy families in Lucca invested in paper manufacturing and, at the end of the 17th century, there were eight paper mills in the province, with emphasis on that of the Tegrimi family, in Vorno. The Tegrimi produced excellent quality paper and maintained commercial relations with foreign countries. There is also the influence of Ligurian papermaking families, such as the Aradi, Peralta and Pollera, who built mills in Lucca, giving rise to different production relations, such as self-management and initiatives to rent buildings for paper manufacturing.

With the large number of mills installed in Lucca, the province faced a time of scarcity of raw materials at the end of the 17th century, the so-called “rag war”. The rag traders, especially the Provenzali and Rapondi, intended to export the product through the port of Viareggio to other markets with better remuneration, but they had to face the businessmen of the paper factories, who demanded that the rags be kept in Lucca. The “war” resulted in a document, signed in 1694, regulating and controlling the export of rags in the province, which was revised years later, in 1700 (Sabbatini, 2013).

Another province in Tuscany that stands out in the paper industry is Pistoia, with production concentrated in Pescia and its surroundings. Sabbatini (2013) describes two paper factories established in Pescia since the end of the 15th century, managed by Antonio di Michele Del Fabbrica, of Genoese origin, in the first decades of the 17th century. The mills then passed to the Ansaldi family, coming from Voltri and commanded by Francesco Ansaldi, who settled in Pescia in 1650 and produced paper until the 19th century. The Ansaldis expanded production to Villa Basilica, Collodi and Colle. We draw attention to Giovanni Battista Ansaldi who, due to services provided in Colle, obtained the license to build two other mills in Pietrabuona, on the outskirts of Pescia, being one in 1710 and the other in 1724.

The great expansion of paper manufacturing in Pescia took place at the end of the 18th century, with the establishment of the Magnani family in the locality in 1783, beginning a fervent period of rentals, purchases, renovations and construction of paper factories, using substantial capital. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Magnani paper factories employed eighty families, shipping their production mainly to Lisbon, Brazil and North America (Sabbatini, 2013).

As previously stated, most of the papers researched come from the current territory of Italy (344 papers, representing 49.35% of the total sample). Of these, 164 come from the Liguria region, 108 from Tuscany and 32 from Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Some papers, totaling forty units, present watermarks referenced in the bibliography and databases as Italian, but without a specific location of provenance. Another 122 papers were classified as “possibly Italian”, due to the design of the watermarks following decorative patterns present on papers identified as Italian.

Papers from the Liguria region

The majority of Italian papers identified in the research sample come from the Liguria region, totaling 164. All papers are from the province of Genoa, 15.85% of them produced in Voltri (26), 1.83% in the commune of Mele (3) and 82.32% did not have the commune identified from the bibliography consulted (135).

As mentioned previously, Voltri, a commune located on the Italian coast and with mighty rivers, stood out in the paper production scene, especially due to its geographical and geological characteristics. Paper mills began to be established at the end of the 15th century, especially on the banks of the Leira and Cerusa rivers, using flax and hemp rags as raw materials. In 1588, forty paper mills were registered, 16 in Gorsexio, 13 in the Leira river valley and 11 in the Cerusa river valley. Already in 1675, the buildings dedicated to paper production in Voltri numbered fifty and, between the 18th and 19th centuries, paper factories grew to reach 102 in 1851 and 160 in 1857 (Dellacasa, 2015).

Part of the Quartino family settled in Voltri, known since the 16th century for being shipbuilders and caulkers (Gatti, 2016). It is not known exactly when the family started in the paper production business, however there are Quartini mills in both Liguria and Tuscany. Among the family’s well-known paper producers, Stefano, Fioretto, Federico and Giovan Battista stand out, who use the letter “Q” to identify the paper of their mills (Santos, 2015).

In the sample collected there are nine in-folios and two folios with the left portion suppressed, containing a coat of arms crowned with a central stripe, in a descending direction, with the inscription “Libertas”, in addition to the monograms “SQ” (six papers) and “GAQ” (five papers) below the coat of arms. The “SQ” monogram identifies the production of Stefano Quartino, however we did not find the name corresponding to the “GAQ” monogram, although such initials are presented by Balmaceda (2016) as being produced by the Quartino family.

All Quartini papers are cream colored and the folios have medium dimensions and very similar weights. The total average of the folios is 30.6 cm high and 42.5 cm wide, with an average weight of 78.4 g/m2, points of 24 mm and bends of 1 mm. All papers have homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface.

Another Voltri paper producer found in the sample is G. B. Fabiani, with little information about its production. According to Balmaceda (2016), the “GBF” monogram is by Fabiani. It appears next to two distinct watermarks in the sample: the first, present in a in-folio (doc 226), is a complementary watermark, presenting the bull and the bullfighter and, below, the letters “GBF” forming an inverted triangle; the second is a watermark with the coat of arms of Genoa and the “GBF” monogram on the lower portion, also arranged in an inverted triangle. Despite not constituting a folio, the main countermark related to this watermark is the inscription “Fabiani”, found on two papers. The composition of the folio can be seen in the inventory by Balmaceda (2016), with the main countermark on the right portion of the folio.

Just as the papers from the Quartino family, those from Fabiani are cream colored, with a homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface. There is only one in-folio measuring 30.6 cm high and 42.2 cm wide. The remaining papers (three units) are folios with suppressed portions, with an average height of 30.7 cm and an average width of 21.3 cm. The average weight of Fabiani papers is 68.9 g/m2, with 24 mm points and 1 mm bends.

Paper production in Voltri gained great prominence and aroused the interest of the Dongo family, from Lombardy, who moved to Genoa in 1375. Headed by Bartolomeo, Giuseppe and Guglielmo, the family built, between 1610 and 1630, a paper mill village in the Cerusa river valley, called San Bartolomeo delle Fabbriche (Dellacasa, 2015). The village had a small palace, a square, a church and no less than 19 paper mills arranged in a cascade, along two artificial canals, in order to take advantage of a waterfall of more than a hundred meters, 17 of which were producers of white paper and two of brown paper (Fahy, 2004).

Due to the Dongo family’s investments in the paper industry in the Voltri commune region and, consequently, in the economic development of the family and San Bartolomeo delle Fabbriche, Bartolomeo and Guglielmo received, in 1629, the title of Liber nobitatis. This document recognizes the prominent socioeconomic position of a given family and lists the citizens eligible to be part of the governing council of the Republic of Genoa (Camanjani, 1965). Guglielmo, the eldest of the three brothers, opened a store with the aim of exchanging paper and Bartolomeo, the founder of Fabbriche, fought for control of the production and sale of paper in the Mediterranean basin. In addition to the construction of paper factories, in the same period Bartolomeo worked on strengthening infrastructure and water supply channels, also acquiring several lands near the Cerusa river (Dellacasa, 2015).

According to Santos (2015), the letter “D” as a mark on the paper identifies the production of the Dongo family. Balmaceda (2016) adds the main countermark with the inscription “S. Bartolomeo delle Fabbriche” also as an identification of the family mills. Among the papers inventoried for this research, we found eight in-folios with the main countermark “S. Bartolomeo delle Fabbriche”, on the right portion of the folio, and the watermark of the Genoese coat of arms, with the inscription, that resembles the letter “J” and the number “6”, arranged in the lower portion of the coat of arms. We also observed three folios which right portion was suppressed, with only the watermark with the coat of arms.

The use of the symbol that resembles a “J” on papers of Italian origin indicates the plural of a word, as can be seen in the marks inventoried by Balmaceda (2016), such as for the plural of the word figli (children, in English). By mirroring the inscription below the coat of arms that accompanies the “S. Bartolomeo delle Fabbriche”, we read, instead of the number 6, the letter “d” and the symbol pointed out, which could be another indication of the Dongo family (“d” for Dongo and “J” for the plural, as in “children of Dongo”).

Among the 11 identified papers produced by the Dongo family, only one of them has a light blue color, the others are all cream. The folios are 30.1 cm high and 42.1 cm wide, with an average weight of 73.4 g/m2, with 24 mm points and 1 mm bends. Most of the papers (seven folios) have a homogeneous distribution of fibers and an ideal surface for writing, however, four other papers, including the blue one, do not have the same quality.

Located about four kilometers north of Voltri, Mele is another paper-producing commune also developed along the Leira River. From Mele we find two producers, Gerolamo Ghigliotti (one folio) and Giuseppe Picardo (two folios).

Gerolamo’s paper was identified by the initials “GG” (Balmaceda, 2016), arranged below the composition of a crowned fleur de lis. The folio, which had its right portion suppressed, is cream colored, with a heterogeneous distribution of fibers and a friable surface. The paper is 31.5 cm high and 21.3 cm wide, with 23 mm points and 1 mm bends, with a weight of 74.6 g/m2.

Giuseppe Picardo’s paper contains complementary watermarks: on the left portion of the folio, there is a sun surrounding the initials “NSDC” and the name “Giuseppe” below; on the right, you can see the “Libertas” coat of arms and the name “Picardo”. In the lower right portion, there is the “GP” monogram as a corner countermark. The other paper produced by Picardo features only the right-hand portion of the in-folio, also accompanied by the “GP” corner countermark. The papers are cream colored, with a homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface, with an average weight of 85.6 g/m2. The folio is 30.5 cm high and 41.8 cm wide, with 2.4 mm points and 1 mm bends.

It is known that Giuseppe Picardo was born in Voltri, where he learned the craft of making paper. He built a paper mill in Mele in 175612 and there are records that part of his descendants migrated to the commune of Fontana Liri, in the Lazio region, running Cartiera Lucernari from 1838 to 1873.13 The mill built by Picardo in Mele operated until 1985 and, in 1997, following initiatives from the municipal administration, the Paper Museum (Il Museo della Carta Mele) was opened, using the local infrastructure. The museum is currently open and offers guided tours and workshops, as well as a manual paper production course.

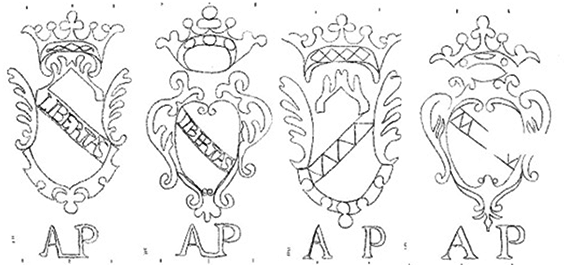

Other producers had mills in the Republic of Genoa, however we do not have specific data on the location of the mills or details of families or production. Most of the papers researched, corresponding to 10.61% of the total sample, are by Andrea (or António) M. Pollera,14 identified with the letters “AP”. We observed four types of watermarks from this manufacturer, all composed of a crowned coat of arms accompanied by the “AP” monogram in the lower portion.

We observed two designs of the coat of arms with the inscription “Libertas” on a central stripe, 48 papers with design A and 21 with design B. Some contain the letters of the monogram “AP” joined, however there is a variation in the letters arranged separately. The other two compositions are similar to designs A and B, but the central stripe features a series of joined triangles. There are four papers with design C and one paper with design D (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – The four designs related to the papers identified with the letters “AP”. Source: APM, CC, cx. 37, pl. 30,096, doc. 1; cx. 32, pl. 10,648, doc. two; cx. 32, pl. 10,649, doc. 3; cx. 82, pl. 20,169, doc. 315

We found 34 in-folios produced by Andrea (or António) M. Pollera with an average height of 30.8 cm and width of 42.6 cm. The average paper weight is 76.5 g/m2, with papers ranging from 53.5 g/m2 to 101.8 g/m2. Most of the papers are cream colored (58 units), but there are also light blue papers (16 units). In general, the paper produced by Andrea (or António) M. Pollera has a homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface (77.1%), suitable for writing.

Still from the Pollera family (Polleri, in the plural) there are papers produced by Pascuale Pollera and Nicolo Polleri. According to Santos (2015), Pascuale Pollera was the founder of Fabrica Nova, a mill established in the Republic of Genoa, and used the letter “P” to indicate its production. Santos also draws attention to the letters “GC” accompanying the Fabrica Nova brand, which could “correspond to the initials of a bidder from that paper unit or the initials of the name of the master papermaker from that same factory” (Santos, 2015, p. 55). In this case, the papers have a fleur de lis on the left portion of the in-folio, accompanied by the letters “GC” and the inscription “Fabrica” (four papers, two of which are in-folios). On the right portion of the paper, there is a Portuguese shield and the inscription “Nova”.15

Fabrica Nova’s in-folio format papers have an average height of 30.9 cm and a width of 43 cm. The weight is 81.4 g/m2, with points distributed at 23 mm on average and bends at 1 mm. All papers are cream colored, with fibers distributed homogeneously and smooth surface.

Also by Pascuale Pollera, we observed three other papers, two with the watermark of the three circles and one with an incomplete coat of arms, due to the configuration of the document’s dimensions. However, all watermarks come with the “PP” monogram, indicating Pascuale production. Another papermaker in the family is Nicolo Polleri. We found only one in-folio with the complete watermark of his papers, containing a crowned fleur de lis and a sun with the initials “SNDB”, in addition to the name Nicole Polleri.

Another five papers show the identification of Nicolo Polleri, but they are folios with suppressed portions and, consequently, incomplete watermarks. There is also a variation of a sword accompanying the name “Polleri”, instead of the sun. All papers produced by Nicolo Polleri are cream colored, have a homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface. The size of the in-folio is 30.7 x 42.1 cm, with an average weight of 64.1 g/m2, points of 23 mm and bends of 1 mm.

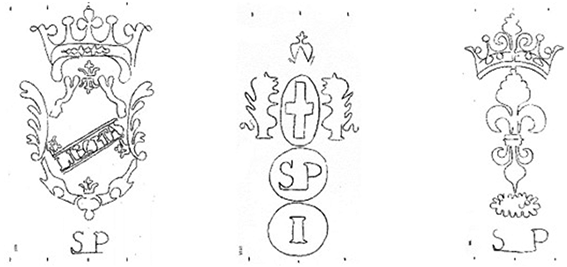

We also found papers by Stefano Patrone, identified by the monogram “SP” (Santos, 2015). There are four watermark designs that include the “Libertas” coat of arms (two folios); the three circles, one being flanked by griffins (one folio) and the other without the presence of this representation (one folio); and, finally, a crowned fleur de lis (Figure 5). All papers are cream colored, with a homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface. The folios (three units) have an average height of 30.5 cm, width of 42.0 cm, weight of 83.7 g/m2, points of 24 mm and bends of 1 mm.

Figure 5 – Examples of watermark designs from Stefano Patrone’s production. Source: APM, CC, cx. 53, pl. 30,417, doc. 3; cx. 10, pl. 10,203, doc. two; cx. 22, pl. 10,445, doc. 2

As Santos (2015) indicates, Stefano Patrone “also uses the monograms ‘GBG’, ‘SADP’, ‘SPDA’, ‘SBP’ and ‘GPG’ to identify his production”. We found two folios with the left portion suppressed, presenting the coat of arms with the inscription “Libertas” and the letters “GBG” in the lower portion, forming an inverted triangle. For papers identified with the “GBG” monogram, the average height of the folios is 30.1 cm; the width is 21.1 cm, with a paperweight of 86.7 g/m2, points of 28 mm and bends of 1 mm. All papers are cream colored and have a smooth surface.

Another family of Genoese origin active in paper production is Gambino, like Andrea and Bernardo, with mills in the Leira valley. The Gambini used the shape of a leg16 as an identification watermark for their production (Santos, 2015). The small leg, with the toe facing to the right, is included in the central circle of the watermark. The two in-folios with the watermarks are cream colored and have a heterogeneous distribution of fibers, but with a smooth surface. The average height of the folios is 31.0 cm, the width is 43.4 cm, with a weight of 74.2 g/m2, points of 25 mm and bends of 1 mm.

In addition to the documents identified by the presence of the shape of the leg, there are 12 papers (three in-folios and nine folios of different dimensions) with the drawing of a male human figure, smoking a pipe, holding a shape similar to a dragon, and, in the lower portion, there is the “SG” monogram. Balmaceda (2016) presents the letter combination “SG” as used in Gambino family papers and, therefore, we classify such papers as originating from Gambini mills.

Like the other two papers from the Gambino family, these in-folios are cream colored, have a homogeneous distribution of fibers and a smooth surface. The average height of the folios is 30.3 cm, the width is 42.6 cm, with a weight of 77.3 g/m2, points of 24 mm and bends of 1 mm.

In the research sample universe, three Genoese paper manufacturers were also identified with their names in their watermarks, namely “Porrata”, “Maineiro” and “Bernardo”. However, no information was found regarding these producers only that their mills are of Genoese origin (Balmaceda, 2016). Another ten Genoese manufacturers use monograms on their papers integrated into watermarks and main countermarks or compose a corner countermark.

We identified the papers with the corner countermark “GBD” as those of Giavanni Battista Deferrari, as shown in the Balmaceda (2016) database, also displaying the complementary marks of the bull and the bullfighter. The paper with the corner countermark “GMT”, located in the lower left portion of the folio, and a coat of arms with a bird in the center was identified as being produced by the Testa family. Among such papers, we note a variety of designs such as the crowned fleur de lis, the rampant lion (whether or not accompanying the crowned fleur de lis), the three circles, the rooster, the “Libertas” coat of arms, the coat of arms of Portugal and the coat of arms with a rampant lion in the center.

After the analyzes carried out, the Ligurian papers proved to be of good quality, with only 23.17% of them having a heterogeneous distribution of fibers and 9.38% having an irregular surface. The majority of the folios are cream colored (144 papers) and the minority have a bluish tone (twenty papers). The average size of the folios is 30.6 cm high and 42.4 cm wide. The average weight of the papers is 75.3 g/m2, with extremes of 60.9 g/m2 (doc 419, with paper by Nicolo Polleri)17 and 106.3 g/m2 (doc 685, with paper by Andrea M. Pollera). The average measurement of the points is 25 mm and the bends is 1 mm.

Final considerations

Paper supports ideas, thoughts and is the basis for communication. For a long time it was almost the only physical medium that circulated information. In the context of the administration of the captaincy of Minas Gerais in the 18th century, the use of paper, transformed into a document, proved to be of great importance for the maintenance of economic, political, social and cultural relations between the Crown and the captaincy and for the relations internal to the captaincy itself.

Based on a bureaucratic system, several types of documents circulated, each with specific characteristics, such as requests, records, certificates, letters, and orders, among others. Currently, these administrative documents are found in custodial institutions, such as the Arquivo Público Mineiro [Public Archive of Minas Gerais], and can be consulted to understand history. However, most researchers who look at documents look for information written on the paper and ignore that which the document itself provides regarding materiality. During the research we understood how the intrinsic marks of the paper, the techniques and materials used, combined with the survey of sources, can be indicators of provenance.

Although there are studies that point to the feasibility of identifying the origin of papers based on watermarks – which in fact proved possible in this research –, there are few published results and, in most cases, they bring just the watermarks designs, without the name of the manufacturer, the mill or the place of production. The available databases share the same problem and essentially become image banks, with little metadata accompanying the graphic information. Likewise, information on paper purchases in the captaincy of Minas Gerais is sparse and decentralized, and few accessible documents deal with the topic.

Even with the difficulties encountered and little information, we identified in the sample one English paper, 21 French, 73 Dutch, 344 Italian and 122 possibly Italian. The remaining papers, with some watermarks that even appeared in the databases, but without other references of provenance, were classified as unidentified. In this way, we highlight here a field of studies lacking researchers. And which, combined with the availability of technologies for analyzing cultural assets, as well as the growing academic training of new professionals interested in researching the material elements of culture, can contribute to the unveiling of issues relating to the ways of making paper, its characteristics and its provenances.

Most of the papers identified in the sample are from the Pollera family, papermakers from Liguria, contradicting the statements by Barata (2017) and Balmaceda (2009) that the most common paper imported by Portugal had the watermark “Gior Magnani”. In fact, Giorgio Magnani’s family established first in the commune of Luca and then in Pescia, sent a large part of its production to the markets of the former Portuguese colonial empire (Santos, 2015). At the beginning of the 19th century, the Magnanis owned five paper factories, including “Cartiera Al Masso” – one of the largest projects built at the time –, three for rent and built one more, in addition to managing a printing plant and a silk factory. The importance of the Magnanis is so great that the company became a supplier to all state offices in all Italian departments and, in 1812, obtained authorization to manufacture paper with the watermark of Napoleon and Maria Luisa of Austria.

Therefore, it is interesting to return to the discussion brought to the research of material culture in which the study of the object itself is combined with the available sources. This combination proved to be very useful for the archival documents researched here, even more so due to the lack of available bibliographic sources that deal, above all, with the paper trade in the Modern Era. Although we find purchase lists of writing materials, including papers, listed in record books of the captaincy of Minas Gerais (Quintão, 2017), as well as individual receipts for purchased folios (Gonçalves, 2021), there are no systematized studies that reveal the commercial routes of paper in the 18th century until its arrival for consumption in the captaincy of Minas Gerais. This gap in the trade of such material is observed in several other countries, including European ones with a tradition in the field of studying the history of paper. Daniel Bellingradt, professor and scholar in the area, highlights the lack of research on the world paper trade in the Modern Era, saying that historians are rarely interested in the subject and that little is known about distribution and logistics networks, traders and the volume of this trade. Contemporary research based on case studies, although insufficient, has contributed to filling this space, but continues to be centered on the European continent (Bellingradt; Reynolds, 2021).

Understanding how to make rag paper was crucial to the characterization of the documentation, we chose to deepen the study regarding the ways of making Italian paper, the origin of most of the folios consumed for the administrative documentation studied. From the study of ways of making paper, we understand that the combination of raw material (pulp, additives and sizing substances) and the specific skills of each mill worker are decisive in guaranteeing the quality of the final product. This aspect is related to the use of paper. Therefore, good paper for writing administrative documents should be smooth, clear, without holes, with homogeneously distributed fibers, well glued, not too thin and not too large.

It is noteworthy that another product of this study is the catalog constructed from the watermarks found in the sample, constituting a research instrument that contributes to the study of the history of paper. The visual documentation of watermarks and the use of standards proposed by IPH to fill in metadata point to a systematization of information, envisioning the expansion of research in the future and the integration of catalogs and inventories from other researchers. In this way, we hope that the information can be shared among paper historians and other researchers, creating support for future research on the topic.

We would like to thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) for the research grant.

Sources

Arquivo Público Mineiro [Public Archive of Minas Gerais]

Inventory of the Casa dos Contos Collection (unbound documents), 2007 revision. Available at: http://www.siaapm.cultura.mg.gov.br/modules/fundos_colecoes/brtacervo.php?cid= 12. Accessed on: 20 Jul. 2015. Casa dos Contos Collection. Separate documents. CC-1 to CC-166.

References

ALMADA, Márcia. Cultura escrita e materialidade: possibilidades interdisciplinares de pesquisa. Pós: revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes da Escola de Belas-Artes da UFMG, v. 4, n. 8, p. 134-147, nov. 2014.

ALMADA, Márcia. Na forma do estilo: normas da boa pena nos séculos XVII e XVIII em Portugal e Espanha. Revista Documenta & Instrumenta, n. 8, p. 9-28, 2010.

ALMEIDA, Thais Helena de; HANNESCH, Ozana. Orianda, a fábrica de papel do barão de Capanema: de 1852 a 1859. In: CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL DE HISTORIA DEL PAPEL EN LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA, 13., 2019, Málaga. Actas... Tomo II. Málaga: Asociación Hispánica de Historiadores del Papel, 2019. p. 95-109.

ASUNCIÓN, Josep. The complete book of papermaking. New York: Lark Books, 2003.

BALMACEDA, José Carlos. Conservación, análisis e historia del papel (Cahip). Available at: http://www.cahip.org. Accessed on: 2 Feb. 2021.

BALMACEDA, José Carlos. La marca invisible: filigranas papeleras europeas en Hispanoamérica. Espanha: Cahip, 2016.

BALMACEDA, José Carlos. Los Magnani: papeles y filigranas en documentos hispanoamericanos. In: CONGRESO NACIONAL DE HISTORIA DEL PAPEL EN ESPAÑA (AHHP), 8, 2009, Burgos, España. Actas... Burgos: 2009. p. 51-70.

BALMACEDA, José Carlos. La contribuición genovesa al desarrollo de la manufactura papelera española. In: CONGRESS-INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PAPER HISTORIANS, 26, 2002, Roma. Paper as a medium of cultural heritage: archaeology and conservation. Roma: Cahip, 2002.

BARATA, Paulo Rui. As marcas d’água do papel selado de Portugal (1661-1668 e 1797-1804). In: CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL HISTORIA DEL PAPEL EN LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA, 12, 2017, Santa Maria da Feira, España. Actas... v. 1, tomo 1. Santa Maria da Feira: 2017. p. 173-189.

BELLINGRADT, Daniel; REYNOLDS, Anna. The paper trade in early Modern Europe: practices, materials, networks. Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2021.

BELLINGRADT, Daniel. Trading paper in early Modern Europe: on distribution logistics, traders, and trade volumes between Amsterdam and Hamburg in the mid-late eighteenth century. Jaarboek voor Nederlandse boekgeschiedenis, v. 21, p. 117-131, 2014.

BELLOTTO, Heloisa Liberalli. Arquivo: estudos e reflexões. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2014.

BERNSTEIN. Memory of paper. Available at: http://www.memoryofpaper.eu/. Accessed on: 12 Mar. 2021.

BOUZA ÁLVAREZ, Fernando. Imagen y propaganda: capítulos de historia cultural del reinado de Felipe II. Madrid: Akal, 1998.

BOUZA ÁLVAREZ, Fernando. Del escribano a la biblioteca: la civilización escrita europea en la alta edad moderna (siglos XV-XVII). Madrid: Síntesis, 1997.

CALEGARI, Manilo. Mercanti imprenditori e maestri paperai nella manifattura genovese della carta (sec. XVI-XVIII). Quaderni Storici, Bologna, v. 20, n. 59, p. 445-469, ago. 1985.

CAMAJANI, Guelfo Guelfi. Il “liber nobilitatis genuensis” e il governo della Repubblica di Genova fino all’anno 1797. Firenze: Società italiana di studi araldici e genealogici, 1965.

CHARTIER, Roger. Os desafios da escrita. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2002.

CHURCHILL, William Algernon. Watermarks in paper in Holland, England, France, etc., in the XVII and XVIII centuries and their interconnection. Amsterdam: Menno Hertzberger & Co., 1935.

CONCEIÇÃO, Adriana. Escrever e arquivar: as cartas do vice-rei 2º marquês do Lavradio – século XVIII. In: SIMPÓSIO NACIONAL DE HISTÓRIA (ANPUH), 27, 2013, Natal. Anais... Natal: 2013.

COSTA, Walmira. Compromissos de irmandades mineiras: técnicas, materiais e artífices (c. 1708-1815). Tese (Doutorado em História) – Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2016.

DELLACASA, Sonia. Le manifatture della carta nelle Valli Leira e Cerusa a Voltri. A Compagna (bollettino trimestrale, omaggio ai soci), Genova, anno XLVII, n. 3, p. 12-16, Lug./Set. 2015.

DOMINGUES, Angela. Para um melhor conhecimento dos domínios coloniais: a constituição de redes de informação no Império português em finais do Setecentos. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, v. VIII (suplemento), p. 823-38, 2001.

FAHY, Conor. Paper making in seventeenth-century Genoa: the account of Giovanni Domenico Peri (1651). Studies in Bibliography, Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, v. 56, p. 243-259, 2003/2004.

FIGUEIREDO, Manoel de Andrade de. Nova Escola para aprender a ler, escrever e contar. Lisboa Ocidental: Oficina de Bernardo da Costa de Carvalho, 1722. Available at: http://purl.pt/107/. Accessed on: 7 Nov. 2014.

FIGUEIREDO JUNIOR, João Cura D’Ars de. Química aplicada à conservação de bens culturais: uma introdução. Belo Horizonte: São Jerônimo, 2012.

GATTI, Luciana. Um raggio di convenienza. Navi mercatili, construttori e proprietari in Liguria nella prima metà dell’Ottocento. Gênova: Società Ligure di Storia Patria, 2016.

GIMPEL, Jean. A Revolução Industrial na Idade Média. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1977.

GÓMEZ, Antonio Castillo. Entre la pluma y la pared: una historia social de la escritura en los siglos de oro. Madrid: Akal, 2006.

GONÇALVES, Marina Furtado. Fazer e usar papel: caracterização material da documentação avulsa da Coleção Casa dos Contos do Arquivo Público Mineiro (1750-1800). Tese (Doutorado em História) – Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2021.

GONÇALVES, Marina Furtado. O tratamento da tinta ferrogálica: estudo de um conjunto de documentos manuscritos sobre papel de trapo da Coleção Casa dos Contos do Arquivo Público Mineiro. Monografia. Graduação em Conservação e Restauração de Bens Culturais Móveis) – Escola de Belas Artes, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2013.

GRIMAL, Pierre. Dicionário da mitologia grega e romana. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2018.

HEAWOOD, Edward. Watermarks mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries. Monumenta Chartae Papyraceae. Holland: The Paper Publications Society, 1950.

HUNTER, Dard. Papermaking: the history and technique of an ancient craft. 2. ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1978.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PAPER HISTORIANS. International standard for the registration of papers with or without watermarks. Version 2.1.1. Denmark: IPH, 2013.

LAURENTIUS, Theo; LAURENTIUS, Frans. Watermarks in paper from the South-West of France, 1560-1860. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2018.

LAURENTIUS, Theo; LAURENTIUS, Frans. Italian watermarks 1750-1860. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2016.

McKENZIE, Donald F. Bibliography & the sociology of texts. Port Chester, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

MELO, Arnaldo Faria de Ataide e. O papel como elemento de identificação. Anais das Bibliotecas e Arquivos (separata dos n. 17 e 18, 19 e 20, 21,22 e 23), Lisboa, Oficinas Gráficas da Biblioteca Nacional, 1926.

MENESES, José Newton Coelho. Cultura material no universo dos impérios europeus modernos. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v. 25, n. 1, p. 9-12, jan./abr. 2017.

MENESES, José Newton Coelho. A semântica de uma memória: os modos de fazer como patrimônio vivencial. In: REIS, Alcenir Soares; FIGUEIREDO, Betânia Gonçalves (org.). Patrimônio imaterial em perspectiva. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2015. p. 169-195.

MILLER, Daniel. Trecos, troços e coisas: estudos antropológicos sobre a cultura material. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2013.

NUNES, Maria de Fátima; BRIGOLA, João Carlos. José Mariano da Conceição Veloso (1742-1811): um frade no universo da natureza. In: CAMPOS, Fernanda Maria Guedes (org.). A Casa Literária do Arco do Cego (1799-1801). Bicentenário: “sem livros não há instrução”. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional; Casa da Moeda, 1999.

QUINTÃO, Régis Clemente. Sob o “régio braço”: a Real Extração e o abastecimento no Distrito Diamantino (1772-1805). Dissertação (Mestrado em História) – Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2017.

REDE, Marcelo. História a partir das coisas: tendências recentes nos estudos de cultura material. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v. 4, p. 265-282, jan./dez. 1996.

ROCHE, Daniel. História das coisas banais: nascimento do consumo nas sociedades do século XVII ao XIX. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2000.

RÜCKERT, Peter; DIETZ, Georg. Testa di bue e sirena: la memoria della carta e delle filigrane dal medioevo al seicento. Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart: 2007.

SABBATINI, Renzo. Di foglio in foglio, uma lunga storia. In: La Via della Carta in Toscana, um progetto territoriale di sistema. Luca: Lucense, 2013.

SABBATINI, Renzo. La manufatura dela carta in Etá Moderna: il caso Toscano. Tese (Doutorado em História) – Instituto Universitario Europeo, Firenze, 1988.

SANTOS, Maria José Ferreira dos. Marcas de água, séculos XVI-XIX: Coleção Tecnicelpa. Tomar: Tecnicelpa (Associação Portuguesa dos Técnicos das Indústrias de Celulose e Papel); Santa Maria da Feira: Câmara Municipal de Santa Maria da Feira, 2015.

SEGREDOS necessários para os ofícios, artes e manufacturas e para muitos objectos sobre a economia doméstica. Lisboa: Officina de Simão Thaddeo Ferreira, 1794.

TOSCANA, LA VIA DELLA CARTA. Storia della carta a Lucca. Available at: http://laviadellacarta.it. Accessed on: 2 Feb. 2020.

Received on March 27, 2023

Approved on May 18, 2023

Notes