Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 36, n. 2, May/Aug. 2023

Marc Ferrez: the photography as an experience | Thematic dossier

Collections for visual studies in a history museum

Colecciones para estudios visuales en un museo de historia / Acervos para os estudos visuais em um museu de história

Solange Ferraz de Lima

PhD in Social History at the University of São Paulo (USP). Associate professor at Museu Paulista, USP, Brazil.

Abstract

This paper discusses the presence of photography in our visual culture from a perspective that emphasizes the preservation of material culture in history museums, and works with some examples of collections and case studies which deal with the uses and social functions of photographs. It seeks to highlight the importance of preserving organic sets of documents that allow multiple approaches able to work with the complex agency of photography in contemporary society.

Keywords: museums of history; photographic heritage; collections; portrait; photography.

Resumen

El artículo aborda la presencia de la fotografía en nuestra cultura visual desde una perspectiva que problematiza la preservación de la cultura material en un museo de historia, trabajando con ejemplos de colecciones y estudios de caso que tratan de los usos y funciones sociales de las fotografías. Se busca resaltar la importancia de preservar conjuntos orgánicos de documentos que permitan múltiples aproximaciones capaces de dar respuesta a la compleja agencia de la fotografía en la sociedad contemporánea.

Palabras clave: museo de historia; patrimonio fotográfico; colecciones; retrato; fotografía.

Resumo

O artigo discute a presença da fotografia na nossa cultura visual de uma perspectiva que problematiza a preservação da cultura material em um museu de história, mobilizando exemplos de coleções e estudos de casos que tratam dos usos e funções sociais das fotografias. Procura-se evidenciar a importância de preservar conjuntos orgânicos de documentos que permitam abordagens múltiplas, capazes de responder ao complexo agenciamento da fotografia na sociedade contemporânea.

Palavras-chave: museu de história; patrimônio fotográfico; coleções; retrato; fotografia.

The welcome initiative of this dossier dedicated to Marc Ferrez and his vast visual output creates a space to reflect on the material legacies that can be mobilized for the study of the presence of photography in society’s multiple dimensions. The intention in this article is to highlight the importance of preserving organic sets1 of documents that allow for multiple approaches, capable of responding to the complex agency of photography in contemporary society.

To what extent can the documentation generated in the processes of production and circulation (such as invoices, goods inventories, ledgers, correspondence, delivery notes, etc.) shed light on the microeconomic sphere of photographic enterprises, namely the specificities of commercial networks, and working and production conditions?

The formation of typological, thematic, and iconological series that documentation accumulated in custodial institutions propitiates, as a methodological step for visual studies, is another important aspect to be considered in visual collection acquisition policy, opening avenues for understanding the ways in which figurative and formal repertoires are disseminated and appropriated in different circuits and socioeconomic strata. How do portraits and landscapes produced widely in the context of the creation and maintenance of individual and collective memories grounded by materiality convey and re-signify formal repertoires present in the stylistic conventions of Western visual culture?

At the other end – of reception – what materials allow us to approach the forms of memory production and bonds engendered by photography and in museums?

And how to register/document this type of documentation of a vernacular character2 which, for this very reason, often lacks indications about its production (authors, producers) and content (identification of places, people, etc.)?

There are many albums, illustrated handwritten books, sets of postcards and portraits, among so many formats and object narratives, which bring as symptoms the gesture of resignification, appropriation and the marks of individuals’ private storylines, transported to public custody spaces. The practice of collecting, from private and individual initiatives to public ones, such as museums, is what ensures the preservation of material culture, which is the protagonist of this affective and ideological dimension.

This article looks at these aspects of the presence of photography in our visual culture – production and commercialization, imagetic circuits, affective appropriations – from a perspective that seeks to problematize the preservation of material culture that bears witness to social uses and functions, mobilizing examples of collections and case studies.

Enterprising photographers: producing and marketing

The collection of Militão Augusto de Azevedo (1835-1905), an actor and photographer from Rio de Janeiro who settled in São Paulo in 1862, is still today, after 27 years at the Museu Paulista/USP,3 the institution’s largest authorial collection. Its acquisition was an important milestone in the consolidation of the new collection policy implemented in the 1990 Master Plan, guided by research lines defined in the field of history and material culture (Lima; Carvalho, 2022). The integration of organic documentary sets is one of the frameworks of this new collection policy, which also has among its premises the valorization of material supports capable of providing the means to understand and problematize, for example, circuits of production and consumption. In other words, it seeks to avoid, specifically in the case of photographic heritage, the acquisition of unique pieces based exclusively on aesthetic values and antiquity. The Militão Augusto de Azevedo collection allowed us to consolidate this path as preferential, and has guided field research for the expansion of the collection ever since.

The Militão collection is valuable not only for its impressive documentation of the diversity of portraits in poses typified by 19th-century portraiture. It is also valuable because it allows us to understand the conditions of production and the trade circuit built by the photographer, thanks to his correspondence with merchants – the owners of bazaars, bookshops –, the producers who supplied his laboratory, and to his posthumous inventory. Furthermore, the albums in which Militão kept copies of his negatives are examples of the aesthetic arrangement dispensed to what would be a mix of inventory to manage his clients (the portraits are numbered, suggesting some correspondence with negatives or a control book) and a catalog of poses and settings.

Because of these characteristics, this collection has been feeding studies that approach different aspects of the photographer’s career in the context of the photography practice of 19th century commercial studios. The pioneering study by Boris Kossoy (1978), which explored the wealth of the copybook, was followed by studies such as Grangeiro’s (2000), which, based on the list of products, utensils and equipment registered as the photographer’s property, traces an overview of the business of photography in the city of São Paulo at the time of its first great urban expansion. The modernization engendered by this urban expansion was the guiding thread for the anthropological view of Militão Augusto de Azevedo’s practice, which resulted in the dissertation that became a book by Íris Araújo (2006, 2010). The network of social relations woven by the photographer, which his copybook of letters enabled access to, was used by Araújo to understand his perceptions of the modern in a city that was distant from the court. The author walks a methodological path paved by Ginzburg (1987), Norbert Elias (1995), and Martins (1992) to analyze the connections between Militão Augusto’s personal perceptions, his repertoire, and the political and social moment of the city. The author’s view of the networks of sociability isolates certain themes and scrutinizes commercial relations mediated by this modern artifact:

Therefore, to verify the way these relations were constituted – mediated, precisely, through the photographs – is part of this study, since they provide the subsidy to verify from what position and to whom Militão expressed his opinions about new situations that, in his time, were important and which so deeply touched him. (Araújo, 2006, p. 16)

Another presence in the copybook is theater activity, to be found in the letters addressed to Jacintho Heller, owner of the Companhia de Teatro Phênix and a friend of Militão’s. In these letters, Militão comments on São Paulo’s cultural life, trying to convince his friend to do a short season between Carnival and Easter (Araújo, 2006, p. 43).

More recently, in a different register, and vertically exploring the use of glass negatives, Roger Sassaki (2021) approaches the same copybook to remake the photographic production of Militão’s São Paulo landscapes, experimenting with the formulas and materials of the 19th century studio. The author made use of Íris Araújo’s transcription, which is available from the Museu Paulista collection. Based on a contemporary field diary, Sassaki presents the challenges of the wet collodion technique, and rehearses his own solutions to the difficulties in finding paper and chemicals, drawing a parallel with similar difficulties experienced by Militão and reported in letters and diaries.

In his Master’s degree, the author recovers more information from the copied letters. For example, that Militão, as well as being a photographer, was also a chemicals retailer, and sold collodion that he made himself, as well as varnishes (Sassaki, 2021, p. 15). The letters feature lists of materials, sales proposals, complaints, and business strategies. In addition to the letters, Sassaki compared the photographer’s practice with photography manuals of the period, and in particular one whose translation was the object of a project initiated but not completed by Militão,4 which served as parameters to gauge the available technical culture. The result is an invitation to understand the production and the trade circuit from a perspective of concrete action, which considers the adaptations and small innovations used to overcome the scarcity of materials, for example. What both studies provide is the possibility of understanding the specificities of the presence of photography outside of European centers.

The three approaches, coming from distinct academic areas – history, anthropology, and photography – but drawing on the same documents, are treated here as examples to emphasize the importance of preserving documents capable of shedding light on the production processes and the networks and trade circuits in what they can be explored, to tell a particular story of the formation of photographic culture, without considering it a simple transatlantic transposition anchored by foreign manuals.

An important referent for this approach to photographic heritage, which was a guide in the curatorial process of the Militão Augusto de Azevedo collection, was the treatment applied to the Beck family collection, which brings together textual documents, photographs, and objects related to the activities of Carlos Beck, a German immigrant who settled in the late nineteenth century in the city of Ijuí, in Rio Grande de Sul. The collection was acquired in the mid 1980’s by the Museu Antropológico Diretor Pestana, linked to the Research Center at the Faculdade de Filosofia de Ijuí. The archival treatment given to the collection was already an indication of a concern that would also become ours, a decade later. The administrative documents – administrative control books, correspondence, among others – gave access to the contexts of production and the trade circuit in the south of the country and within an immigrant community, providing the framework for understanding the geographical scope of the photography agency (Canabarro, 2011).

Another important point to be highlighted is the link between these actions of preservation of photographic heritage and the university. In an article published in 1994 in the Anais do Museu Paulista, we had the opportunity to disclose a bibliographic balance on studies about photography in Brazil (Carvalho; Lima et al., 1994). At that time, we pointed out a growing trend of dissertations and theses that used photographic sources in a wide range of themes and methodologies. What became very evident in the 21st century was not only this trend, which is still significant in the field of human sciences, but also the growing interest in curatorial practices of preservation and diffusion of photographic heritage. The case of the Beck collection, valued as an organic set and explored by professors, postgraduate, and undergraduate students in institutional projects at universities, which was an exception in the 1980s, has become more common in the last decade.

In the seminar Aos milhares: desafios da curadoria de grandes acervos fotográficos [By the thousands: challenges in the curation of large photographic collections], organized by the Instituto Moreira Salles, Museu Paulista (University of São Paulo – USP) and the State University of Campinas (Unicamp), in 2020,5 for the occasion of the Peter Scheier exhibition opening (curated by Heloisa Espada), we brought to the discussion case studies that present this profile, in the context of the massive photographic production of the mid-twentieth century. The event was able to demonstrate, beyond the Rio-São Paulo axis, this fruitful collaboration between universities and state or municipal public institutions. The curatorship of the Foto Bianchi fund is an example: for almost ten years the historian, photographer and professor at the State University of Ponta Grossa, Patrícia Camera, has been developing conservation, cataloging, and research activity, qualifying the collection of over forty thousand glass and acetate negatives from Luís Bianchi’s studio. The collection includes precious field notebooks and other documents that record the daily practice of three generations of the Bianchi family at the forefront of photographic study, today preserved at the Casa de Memória de Ponta Grossa. This is an ongoing process of training undergraduates and postgraduates supported by the premises of an approach that takes into account the organicity of the photographer’s collection, which is capable of supporting research on the uses of glass negatives (Camera; Lima, 2018).

A similar approach can be seen in the treatment process of the Alois Feichtenberger (1908-1986) collection, which is now part of the Museu da Imagem e do Som de Goiás (MIS-GO). The German photographer’s legacy was acquired for MIS-GO in 2006, and became an expressive personal archive of his activity – there are thousands of negatives, slides, enlargements, as well as diaries, personal documents, a library, and a hemerotheque. The preservation and cataloging of the collection were funded by the National Bank for Economic and Social Development – BNDES (2007-2010), through a project that brought together a multidisciplinary team of professionals in the areas of museology, archival science, librarianship, conservation, and history (Talarico, 2014). The trajectory and musealization of the collection became the subject of Guilherme Talarico’s doctoral thesis (2018).

From the Greek column to the urban lamp-post: typological series and visual strategies of self-representation

Another premise that structures the photographic collection acquisition policy of USP’s Museu Paulista is the formation of typological series of portraits and urban landscapes. When the Militão collection was acquired, the museum already had a significant collection of portraits produced with various techniques, but with an emphasis on paintings and photographs. Acquisitions have continued over the last thirty years. Today, the collection includes about twenty thousand portraits of various techniques – photography, painting, engraving, printed reproductions, drawings – over a time span of 160 years (1850-2010). Even if we isolate only the photographic portraits (and their variations of printed reproductions), counting not only professional photographers’ portraits, but also vernacular production, the universe is still highly representative of the practice of portraiture in contemporary times. The investment in this typology of production, between professional and vernacular approaches, has resulted in a diversity that offers the potential to discuss what has changed and what has remained in the formal and material strategies of portraiture, understood as a “fictional image” (Fabris, 2004, p. 11) or as a theatrical act (Silva, 2008, p. 29), over time and across a social spectrum that extends beyond social and economic elites.

To exemplify the potential for preservation of photographic heritage guided also by the premise of formation of typological series, I share here the first and still provisional incursions of formal analysis of an iconographic set recently incorporated to the Museu Paulista collection. It is a family album that integrates the Nery Rezende collection, donated to the museum in 2022 and which represents, today, the institution’s largest personal collection, comprising over nine thousand items including notebooks, correspondence, various printed materials, invoices, recipes, photographs, negatives, photo albums, as well as personal and household objects (crockery, Christmas decorations, personal ornaments, household appliances).

The Nery Rezende collection meets all the premises of the acquisition policy, but one in particular merits special attention, as it represents an important qualitative (and quantitative!) inflection in the mission pursued by the museum’s curatorial teams – to make the collection more inclusive and representative of Brazilian society. This is an important inflection if we consider the 100-year history of accumulating collections and documents almost exclusively from the wealthiest layers of society, which only began to change during the 1990s thanks to the acquisition policy outlined in the Master Plan. It is the first personal collection of a black woman, a worker in industry and commerce, a militant of social movements, who lived and worked in São Paulo, integrating her life with the intense process of metropolization that took place in the 1950s and 1960s. The collection also includes a dossier of documents accumulated by Nery concerning her sister, Alice Rezende, an actress in São Paulo’s black theater directed by Abdias do Nascimento.6

The collection was donated by her daughter, Greissy Rezende, and facilitated by anthropologist and educator Alexandre Bispo, who studied Nery Rezende’s life and her process of documental accumulation in his doctoral thesis, which he presented in 2018. The life of Nery Rezende (1930-2012), especially her early years, is similar to that of many Brazilians affected by social and economic inequality. The many stories of large families whose sons and daughters are raised by godmothers or other families are well known. Or girls as young as 13 who are assigned domestic work as nannies, cleaning ladies, and kitchen assistants. Nery went through these first stages, but broke the cycle when she turned 18 by leaving the house where she worked in the ambiguous condition of godmother and goddaughter, but carrying out the duties of a nanny. Nery moved in with her mother and sister in the Bela Vista neighborhood in downtown São Paulo. She became a factory worker at Indústrias Reunidas Francisco Matarazzo (Bispo, 2018, p. 50) and it is at this moment that her concern with accumulating documents of her life in the metropolis began:

It was because she began paid work that she could, along with her mother and sister, have an address of her own. Contributing her wages as a worker to the maintenance of domestic life was fundamental to the affirmation of this new Nery who, like Alice, liked the radio, printed magazines, theater, cinema, and photography; cultural and leisure practices that would prove decisive in the directions her life would follow, for what I now call the Nery Rezende collection was conceived in this passage from living under a favor to living free from the ties and dependencies of the family that raised her in the city. It is not by chance that in the passage from the 1940s to the 1950s, she will retain the testimonies she can about herself, her mother, her sister, her relatives, and friends, which ends up revealing the ways she (they) found to constitute a self and to inscribe and integrate herself into the world and the city; this is why it is so important at times to write one’s own name on magazines of the nascent mass culture that will consolidate at that moment (Almeida, 1997; Ortiz, 2006; Arruda, 2015). (Bispo, 2018, p. 50)

The hypothesis that Bispo raises to understand the motivations of Nery’s process of accumulation, which resulted in thousands of documents added to the museum’s collection that document not only her life in the city, but also the lives of those who were part of her extended family and support network, is correct.

The set of documents reached the museum in good condition and had already had a first archival classification arrangement, prepared by Bispo with the help of Greissy Rezende and a small team that worked with him throughout his doctoral research. Once again, it is worth pointing out how the involvement of post-graduate students with heritage preservation is becoming more and more common, imbricating collection, document treatment, and academic research. And, for the museum teams, the integration of this collection during the celebrations of the bicentennial of Independence is symbolic.

The Nery collection is now available for other studies to be added to Alexandre Bispo’s, and will certainly attract the attention of researchers in the fields of history, anthropology, sociology, and museology. In order to explore the potential of this type of collection and to understand the updates in the patterns and conventions of photographic portraiture throughout the 20th century, I present an exercise in reading a small series of portraits from the family album organized by Nery Rezende.

The “green album” was the first document presented to anthropologist Alexandre Bispo when he visited Greissy to learn about the archive. He recounts: “My first and greatest surprise at the sight of this album was to see so many black people in photographs, and even more so in photographs arranged inside an album conventionally structured to display them” (Bispo, 2018, p. 20). The researcher, who had studied a collection of photographs of a white working woman also living in São Paulo (Mapas fotográficos: memória familiar, sociabilidade e transformações urbanas em São Paulo (1920-1960), 2012), was initially interested in the photographic material, until he understood that it was a (small) part of the huge set amassed by Nery.

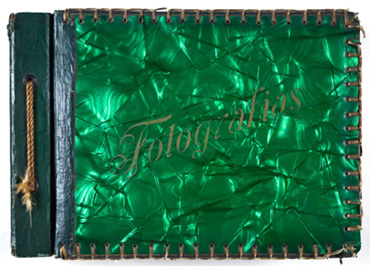

Figure 1 – Album cover and back cover. Reproduced by José Rosael. Nery Rezende/Museu Paulista collection (USP)

The album, which is in landscape format, with cardboard sheets and bound with strings, has a cover made of a textured and shimmering green material with exposed stitching on the edges, and a back cover made of a dark green, seamless leather-like material. Inside, the arrangement combines photographs of various sizes and colors, typical of albums assembled over the course of a lifetime. Its characteristics make it very close to typical family albums, such as those analyzed by sociologist Armando Silva (2008) in his sociological research on photo albums (180 albums researched) conducted with families in three cities in Colombia – Bogotá, Medellin and Santa Marta – and one city in the United States – New York (given the expressive community of Colombian immigrants in the city).

Besides the most recurrent characteristics, Bispo observes and reports his astonishment when coming across an album in which most of the people portrayed are black and points out the reason: “This is because, Miriam Moreira Leite teaches, the practice of organizing photographic memory by means of albums was restricted to the wealthy social classes until the first decades of the 20th century” (1993, p. 75). This perception has its foundation, but another hypothesis is to consider that this happens not because black families did not produce their albums, but because they did not reach museums and archives and did not constitute, in a more expressive way, objects of anthropological research. The family albums depend, of course, on economic conditions, but also on the stability of family networks for the creation of spaces to weave memories and identity processes through material supports and, in the same way, they depend on the extended networks that may contribute to destine such documents to museums or other custodial institutions.7

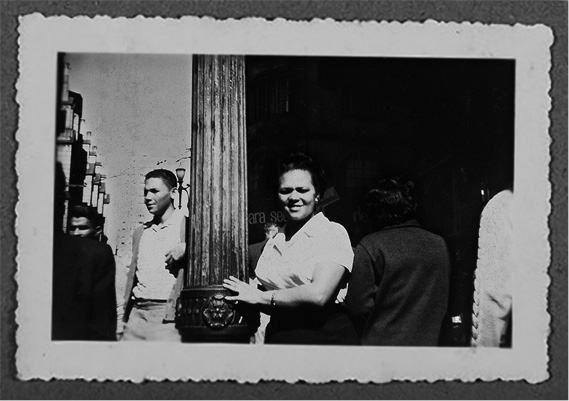

In a general sense, Nery Rezende’s album presents established recurrences – rites of passage (identified by group photographs, a festive domestic setting), journeys, and portraits with dedications. One difference distinguishes the album among those collected and preserved by the museum – the presence of images of work environments, such as store and warehouse interiors. And it is from this particularity that I propose a brief analysis exercise.

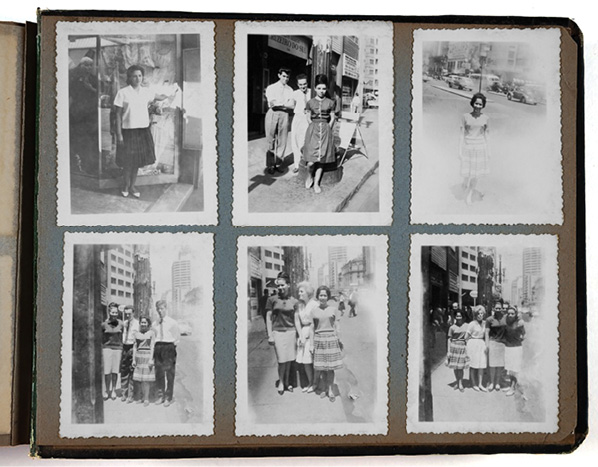

The album contains about 180 portraits. There are no landscapes. In the outdoor photographs, cities, beaches, gardens, and backyards function as the background that frames the portrait, similar to the panels in photographic studios, and here one can already make a first approximation with 19th century standards, the starting point for this exercise on the appropriations of the conventions of portraiture.

The migration of conventions between artistic circuits, configuring comprehensive formal standards capable of updating meanings and values, was one of the issues we were able to address from the vast series of portraits from the Militão Augusto de Azevedo collection, in the jointly developed curatorship with Vânia Carneiro de Carvalho. The quantitative analysis, based on descriptors adopted to enumerate the elements of scenery and gestures of the poses of the portraits cataloged in the digital repository of the Museu Paulista allowed us to control the gender differences in the presentation of the bodies and the recurrences of scenographic elements and gestures in individual, duo, generational, and group portraits. Standards were considered from observed recurrences, in dialogue with a bibliography focused on the forms of representation of the individual, especially those that discuss formal strategies and their material supports such as Mauad (1990), Bruneau (1982), Pointon (1993), Brilliant (1991), Fabris (1993) and Moura (1983). Among the formal references, we identify the process of re-signification of conventions derived from eighteenth-century portraiture, especially scenographic elements inspired by classical architecture such as balustrades, columns, and pedestals:

The presence of classical ornamentation refers to an association cultivated by European aristocracy, making it equivalent to notions of refinement and good taste. Emptied of those specific meanings that were behind the composition in the paintings of noblemen participating in the Grand Tour, these ornaments remain as signifiers (plastic elements, forms) in the composition of the photographic portrait, fulfilling, however, other functions and being re-signified by new urban practices and ascendant bourgeois social groups – the distinction between manual and intellectual labor, introduction to the cosmopolitan and modern world, elegance etc. (Carvalho; Lima, 1997, p. 62)

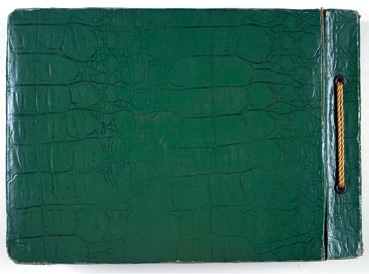

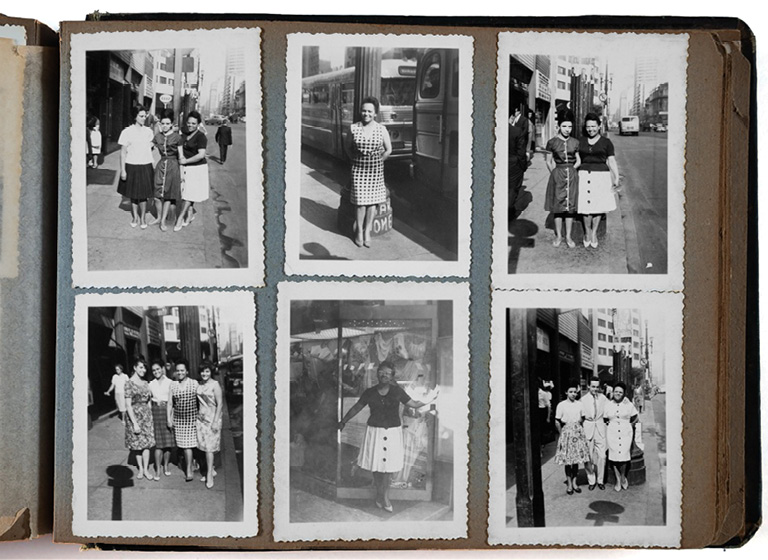

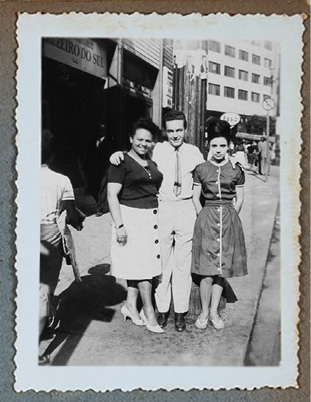

It was surprising to identify how these formal resources could survive in contexts that are distant in time and in type of photographic practice, which was no longer restricted to the studio nor the professional photographer. In the album arranged by Nery Rezende, which includes many photographs perhaps of her own authorship, one series stands out for choosing a lamp-post (located on Avenida São João) as a scenographic element that structures the formal arrangement of the portraits. The post was in front of the Capri store where Nery worked, first as a clerk and then as a manager, for over ten years (Bispo, 2018, p. 90). Full-body portraits with the same setting, an open-air studio, occupy several pages of the album, indicating a systematic way of recording friends (co-workers?). Nery seems to inaugurate the series “pose with pole”, the only one in landscape format, in which the pole appears on the left. As a structuring element of the photographic frame, the pole performs a function similar to that of scenography, such as columns and pedestals, so recurrent in the nineteenth-century studio.

Figure 2 – Nery Rezende and lamp post on Avenida São João. Author unknown, 1950s. Reproduced by José Rosael. Nery Rezende/Museu Paulista collection (USP)

On the following pages of the album, the sidewalk and the lamp post become the synthesis of the studio, where Nery is present either by herself or with colleagues. Only three images use the store where she worked as a background. The set could easily be characterized as a photographic essay, which updates the repertoire of conventions for the scenery of the mid-1950s São Paulo metropolis. Wouldn’t the choice of an urban setting be another way for Nery to inscribe herself in the city, to be part of this modern consumer society, in a movement similar to her archival practice, as defined by Alexandre Bispo?

The formal renewal performed in this "essay", in turn, presupposes knowledge of a plastic repertoire, but in what context? Other family photographs from the 19th century? What meanings did they convey? Certainly other meanings, very different from those that guided the scenographic choices of 19th century studios (the construction of the public image of the bourgeois, for which classical elements indicated good taste and dignity). Could it be possible to think of a kind of premeditated critical citation by Nery Rezende?

This question is not out of context if one considers the involvement of Nery Rezende (and of her sister, Alice Rezende) with theater. Both were, during the same period when the portraits were produced, members of Abdias do Nascimento’s Teatro Experimental do Negro company in its São Paulo incarnation. These are speculations for which we may never find answers. But the possible typological series to be drawn from massive collections, however, allow us to foment studies in the direction of this brief exercise.

Figure 3 – Page from the album Fotografias. Nery Rezende and anonymous people, 1950s. Reproduced by José Rosael. Nery Rezende/Museu Paulista (USP) collection

Figure 4 – Portraits from the album Fotografias. Nery Rezende and anonymous people, 1950s. Reproduced by José Rosael. Nery Rezende/Museu Paulista (USP) collection

Figure 5 – Page from the album Fotografias. Nery Rezende and anonymous people, 1950s. Reproduced by José Rosael. Nery Rezende/Museu Paulista (USP) collection

Figure 6 – Page from the album Fotografias. Nery Rezende and anonymous people, 1950s. Reproduced by José Rosael. Nery Rezende/Museu Paulista (USP) collection

In the examples of collections and archives discussed here we were able to show how the potential for visual studies is linked to the mode of treatment and the acquisition policy implemented at the Museu Paulista. But one of the aspects of curatorship in history museums that is still a challenge for us is how to document the mediation of the processes of transcendence of objects (three-dimensional or two-dimensional) from the private spaces in which they were consumed, used, and signified, to the institutional public space. Although we can be guided by the premises of the acquisition policy as institutionally defined, we still lack protocols to ensure that future researchers can also explore musealization in this micro dimension of personal contacts, of the networks that the museum itself creates, and the ways in which it is a vector that provokes the movement and the desire to be part of history, through the donation of intimate and affectively charged documents. And this aspect especially needs to be considered in the case of photographic documents of a vernacular nature, many of which lack information that allows recording of iconological content and their contexts of production and circulation. It is a challenge that demands preparation from the team that receives the documentation to capture the affective marks capable of providing clues about social uses, expectations in relation to the institution, and even the political meanings of the act of museum incorporation.

In the case of the Nery Rezende collection, for example, there was a desire, expressed by the process mediator Alexandre Bispo, to make explicit the political significance of acquiring the collection of a black woman, marked by racism and social inequality, as an act of militancy, which the museum, by accepting the donation, is also adopting. How to make this condition evident in the musealization process and in the dissemination of the collection, for the researchers who will make use of it?

In the case of the Militão collection, the family and researchers who already knew the documentation expected recognition of the photographer and his full integration into history legitimized by a museum. And they paid attention to the investment made in the collection, as this was the index of this recognition.

There are numerous examples, as there are donor profiles. In the compendium about museums edited by Figueiredo and Vidal (2005), we had the opportunity to discuss this challenge, using donation processes as examples, with attention to the motivations of donors when selecting objects, papers, and images to offer to a history museum (Lima; Carvalho, 2005). We analyzed exemplary cases that pointed to the fecundity and complexity of this specific phenomenon, of the promotion of objects from the private sphere of life to the public sphere and, mainly, the need to document their motivations. The relationship between museum and private collectors was the object of a seminar, an initiative of the Museu Histórico Nacional, which was made into a book (Magalhães; Bezerra, 2012), where a specific section (De colecionadores) considers the motivations around collecting practices which go back centuries, but always keep their historical specificities (p. 10).

Within the process of mediation between the institution and the donors, historicizing the collection and understanding the motivations of the processes of donations and/or sales of objects, images, and textual documents to custodial institutions, we continue to seek means capable of providing information about these practices, because this is how musealized sets also become testimonies of their birth time as public heritage. It was in this context that historian Ana Carolina Maciel developed a postdoctorate at Museu Paulista, which resulted in the production of three documentaries (available at Labhoi/UFF, RJ)8 that capture, from the donors’ perspective, the affective and emotional charge involved in the donation process. Material things matter and are implicated in social life; the moment of collection is precious for understanding this dimension of value.

We can no longer think about the uses and social functions of photographic images without taking into account, on the one hand, how this material legacy of more than a century is constituted and, on the other hand, the affective agency that entangles the histories of individuals and of centennial museums.

References

ARAÚJO, Íris Moraes. Militão Augusto de Azevedo: fotografia, história e antropologia. São Paulo: Alameda, 2010.

ARAÚJO, Íris Moraes. Versões do “progresso”: a modernização como tema e problema do fotógrafo Militão Augusto de Azevedo (1862-1902). Dissertation (Masters in Anthropology) ‒ Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2006.

BATCHEN, Geoffrey. Vernacular photography. In: BATCHEN, Geoffrey. Each wild idea: writing photography history. London; Cambridge: The Mit Press, 2002. p. 56-82.

BISPO, Alexandre. Os percursos da memória e da integração social: o arquivo de Nery e Alice Rezende. Thesis (Doctorate in Anthropology) ‒ Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018.

BRILLIANT, Richard. Portraiture. London: Reaktion Books, 1991.

CAMERA, Patrícia; LIMA, Solange Ferraz de. O outro lado da imagem: o negativo como objeto de conhecimento. Domínios da Imagem, Londrina, v. 12, n. 22, p. 22-46, jan./jun. 2018.

CANABARRO, Ivo dos Santos. Dimensões da cultura fotográfica no sul do Brasil. Ijuí (RS): editora Unijuí, 2011.

CARVALHO, Vânia Carneiro de; LIMA, Solange Ferraz de. Cultura material e coleção em um museu de história: as formas espontâneas de transcendência do privado. In: ELIAS, Nobert. Mozart, sociologia de um gênio. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1995.

CARVALHO, Vânia Carneiro; LIMA, Solange Ferraz de et al. Fotografia e história: ensaio bibliográfico. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v. 2, p. 253-300, jan./dez. 1994.

FABRIS, Annateresa. A fotografia oitocentista ou a ilusão da objetividade. Porto Arte: Revista de Artes Visuais, Porto Alegre, v. 5, n. 8, p. 7-16, nov. 1993.

FIGUEIREDO, Betânia Gonçalves; VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves (org.) Museus: dos gabinetes de curiosidades à museologia moderna. Belo Horizonte; Brasília: Argumentum; CNPq, 2005.

GINZBURG, Carlo. O queijo e os vermes: o cotidiano e as ideias de um moleiro perseguido pela Inquisição. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1987.

GRANGEIRO, Cândido Domingues. As artes de um negócio: a febre photographica ‒ São Paulo, 1862-1886. Campinas: Mercado e Letras, 2000.

KOSSOY, Boris. Militão Augusto de Azevedo e a documentação fotográfica de São Paulo (1862-1887): recuperação da cena paulistana através da fotografia. Dissertation (Masters in Sciences) ‒ Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1978.

LIMA, Solange Ferraz de. A41: breve história de um armário de doações e suas implicações. História: Questões e Debates, v. 61, p. 155-175, 2014.

LIMA, Solange Ferraz de; CARVALHO, Vânia Carneiro de. Cultura visual e curadoria em museus de história. Estudos Ibero-Americanos, Porto Alegre, v. 31, n. 2, p. 53-77, 2005.

MAGALHÃES, Aline Montenegro; BEZERRA, Rafael Zamorano (org.). Coleções e colecionadores: a polissemia das práticas. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Histórico Nacional, 2012.

MARTINS, José de Souza. O dia da caça: o cotidiano das relações de classe num caso de duplo homicídio em 1928. In: MARTINS, José de Souza. Subúrbio: vida cotidiana e história no subúrbio da cidade de São Paulo ‒ São Caetano, do fim do Império ao fim da República Velha. São Paulo; São Caetano do Sul: Hucitec, 1992.

MAUAD, Ana Maria. Sob o signo da imagem. Thesis (Doctorate in History) – Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, 1990.

MOURA, Carlos Eugênio Marcondes de (org.). Retratos quase inocentes. São Paulo: Nobel, 1983.

ORVELL, Miles. Photography and the artifice of realism. In: ORVELL, Miles. The real thing: imitation and authenticity in American culture, 1880-1940. Chapel Hill; London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

POINTON, Marcia. Hanging the head: portraiture and social formation in Eighteenth Century England. London; New Haven: Yale University Press,1993.

SASSAKI, Roger Hama. Pelos caminhos de Militão. Dissertation (Masters in Communication) ‒ Escola de Comunicações e Artes, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2021.

SILVA, Armando. Álbum de família: a imagem de nós mesmos. São Paulo: Senac, 2008. p. 29.

TALARICO, Guilherme. Do acervo à fotobiografia: flagrantes da vida de Alois Feichtenberger (1908-1986). Thesis (Doctorate in History) ‒ Universidade Federal de Goiânia, Goiânia, 2018.

TALARICO, Guilherme. O acervo Alois Feichtenberger: estudo de caso sobre a preservação, inventário e difusão de acervos fotográficos e documentais. In: SIMPÓSIO NACIONAL DE HISTÓRIA CULTURAL, 7., 2014, São Paulo. Anais... São Paulo: USP, 2014.

Received 4/11/2022

Approved 2/5/2023

Notes

1 The organic set of documents refers here to the principles of archivistics, especially that of provenance. At the Museu Paulista, these principles are adopted in the descriptive treatment of funds and collections, both for the institutional collection (Museu Paulista and Museu Republicano funds) and for donated or acquired sets. It is this perspective that defines, for example, the name of the collection or archive, guides its history (recorded in cataloging) as well as the notations that permit the digital recovery of the set.

2 The term vernacular is adopted here from the conceptualization proposed by Geoffrey Batchen in Each Wild Idea (2002, p. 56-82). Batchen defines vernacular photography from a provocation to critical reflection on the history of unique photography, guided by the technical categories of work, artist, and critical fortune. Vernacular are “ordinary photographs, the ones made or bought (or sometimes bought and then made over) by everyday folk from 1839 until now, the photographs that preoccupy the home and the heart but rarely the museum or the academy” (p. 56).

3 The Militão Augusto de Azevedo collection comprises 12,300 photographs (including landscapes and portraits, with a predominance of the latter), a copybook of letters, a diary, and books. It was the object of a donation sponsored by the Roberto Marinho Foundation and TV Globo in 1996, after mediation by the researcher Carlos Eugênio Marcondes de Moura between the administration of the Museu Paulista (under Ulpiano T. B. de Meneses) and the family. The curatorship of the collection was developed by Vânia Carneiro de Carvalho and myself.

4 The collection preserves the incomplete manuscript of the translation of the manual authored by Alphonse Liebert, La photographie en Amérique: traité complet the photographie pratique. Paris, Lieber Libraire-Éditeur, 1864.

5 By the thousands: challenges of curating large photographic collections. Organized by Heloisa Espada, Iara Schiavinatto, Solange Ferraz de Lima. Program: Digital curatorship and LGBTI+ memory: the impacts of digitalization on the collections of social movements of the Edgard Leuenroth Archive, by Aldair Rodrigues (Edgard Leuenroth Archive, Unicamp, SP); Curatorship of the Fundo Foto Bianchi: organization, conservation, and documental treatment of gelatin and silver negatives on glass, by Patricia Camera (Fundo Foto Bianchi, PR); A large-scale curatorship: challenges and delights of managing photographic collections, by Aline Lopes de Lacerda (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, RJ); The Fundo Última Hora of the Public Archive of the State of São Paulo: production, accumulation, and circulation of a press archive, by Bruno Roma (Public Archive of the State of São Paulo, SP); The Alois Feichtenberger Collection at the Museum of Image and Sound of Goiás, by Guilherme Talarico (MIS-GO); The Militão Augusto de Azevedo collection and the process of team qualification at the Paulista Museum of USP, by Solange Ferraz de Lima (Paulista Museum, USP, SP). Available at: https://ims.com.br/eventos/seminario-aos-milhares-desafios-da-curadoria-de-grandes-acervos-fotograficos-2020/.

6 Abdias do Nascimento (1914-2011) was a writer, artist, and playwright who worked at the confluence of artistic proposals and militancy in the black movement. The Teatro Experimental do Negro company was active for over twenty years, mainly in Rio de Janeiro, but also in São Paulo. Sisters Alice and Nery Rezende were part of the company. Nery did not continue and Alice died prematurely.

7 The active stance of custodial institutions is equally important, and may be the path to activate networks of interest, through projects guided by an acquisition policy. At the Museu Paulista, throughout the 2000s, there was an identifiable movement in this direction, as a result of the dissemination of the acquisition policy and of donations and acquisitions that affirmed the desired profile for the collections.

8 Ana Carolina Maciel. Cultura material, percursos autobiográficos: entrevistas com doadores do Museu Paulista da USP. Supervised by: Cecília Helena de Salles Oliveira. Museu Paulista, USP, 2010-2014. Support: Fapesp. The post-doctoral resulted, among other products, in three documentaries: Herança, legado material e memória: imagine um mundo sem rótulos (Egydio Colombo collection); Edmea, Beth e Edith Jafet; Catarina, Ina, China.

Esta obra está licenciada com uma licença Creative Commons Atribuição 4.0 Internacional.